ברוכים הבאים לספר ״ויקרא״ (English below)

ספר ויקרא גם הוא, כמו ספר שמות, מתחיל באות וו, כמעין המשך למה ששמענו עד כה: בספר שמות הבורא קורא לנברא דרך הניסים, מעמד הר סיני ועשרת הדברות, ובניית המשכן שיתן מקום לשכינה בעולם הזה, ואילו ספר ויקרא – כשמו (העברי) כן הוא: הנברא נקרא להתקרב אל הקב״ה. לכן כאן מוזכרת ומתחדשת עבודת הקורבנות – קרבן מלשון להיות יותר קרוב.

רוב הקרבנות היו מן החי, ומעלים פליאה: איך הקרבת בעל חיים יכולה לקרב אדם אל הקב״ה? מה הקשר?? נכון, לא כל שחיטה מקרבת, ובמקום בו נמצא הפוטנציאל הכי חזק לקרבה וטוהר, נמצאת גם האפשרות לבדיוק ההיפך.

ניקח צעד אחורנית: הנפש והגוף, על דרך המשל, הם כמו נהג ברכב שכור. לו שאלנו את הנהג – הנפש – מה היא רוצה, אולי הייתה אומר – לעוף ולהגיע מייד ליעד הנכסף, אך בגלל שהיא תלויה ברכב, כלומר בגוף, היא צריכה לנוע לפי קצב הרכב וחוקי התנועה. והנמשל? אילו היינו שואלים אך ורק את הנפש הטהורה מה היא רוצה, אולי היתה אומרת לנו שהיא רוצה רק לשוב ולהיות עם הבורא.

לכן נאמר בתחילת ספר ויקרא: ״אָדָ֗ם כִּֽי־יַקְרִ֥יב מִכֶּ֛ם קרְבָּ֖ן לַֽה׳״ – אם האדם היה רוצה להקריב – להתקרב, אולי היה מקריב את עצמו, את האדם כולו, אך כבר למדנו מעקידת יצחק, שגם אם האדם מוכן, אל לנו חס וחלילה בשום אופן לעשות דבר כזה. אלא ״מִן־הַבְּהֵמָ֗ה מִן־הַבָּקָר֙ וּמִן־הַצֹּ֔אן תַּקְרִ֖יבוּ אֶת־קרְבַּנְכֶֽם״ (המשך אותו הפסוק בויקרא א,ב). הקב״ה רוצה שנבחר בחיים ומספיק שתהיה לנו כוונה ומוכנות לתת את חיינו. אז בעל החיים ישמש כתחליף.

נשאל עוד: אם ״רחמנא ליבא בעי״ (הקב״ה רוצה את הלב) וכל מה שצריך זו ״כוונה״, אז בשביל מה גם בעל חיים? מה עם ״צער בעלי חיים״?

התשובה על כך אינה תמיד מספקת, כי אנחנו חיים בחברה שונה מאד מהחברה בה ניתנה והתקיימה התורה במלואה, ובכל זאת, אנסה:

התורה עצמה מתייחסת ללקיחת חיי בעל חיים מאד בזהירות. בתחילה בגן עדן, היו כל בני האדם ובעלי החיים טבעונים-צמחונים. אכילת הבשר הגיעה כמעין פשרה אחרי סיפור המבול ותיבת נח. גם כשבני ישראל היו במדבר, נאמרו דברים נגד אכילת בשר ״סתם״, וב״סתם״ הכוונה אפילו למאכל, שלא לדבר על חוקי הכשרות שצמצמו אכילת בשר עוד. מי שרצה לאכול בשר, היה צריך לעשות זאת בקדושה, ובד״כ גם לשתף באכילתו אחרים (קרבן חטאת – לכהנים, קרבן פסח – למשפחה ו/או קבוצה גדולה). אין לי ספק שכמות אכילת הבשר קטנה מאד נוכח החוקים הרבים שסבבו אותה. נהפוך הוא: כיום בניתוק גדול הרבה יותר, כשכל מה שצריך זה ללכת לחנות, לקחת גוש ורדרד כלשהו, לשים אותו ברוטב או על האש, ולא לחשוב על זה שזה היה יצור חי, פועה, מלחך עשב להנאתו בשדה.

המדרש תוהה, אילו היינו יכולים לשאול את בעלי החיים, מה הם היו אומרים? בהפטרה לפרשת ״כי תישא״, מובא סיפורו של אליהו הנביא שבחר להקריב שני פרים במאבק נגד נביאי הבעל. הפר של אליהו הלך אחריו אך הפר שהובא לשם הבעל התנגד בכל תוקף. כשנשאל הפר למה, אמר שהוא לא רוצה לעלות על המזבח כדי להכעיס את הבורא! כלומר, מילא לעלות לקרבן, זה גרוע, אבל לפחות למטרה נעלה ולא בשביל שטות?! זהו הקשר שנעשה גם כיום – הקרבת חיים למען מטרה נעלה נחשבת עדיפה על הקרבת חיים ״סתם״. כך גם, רק כשאליהו הבטיח לפר השני ששמו של הקב״ה יתקדש גם על ידו, הסכים ללכת.

התורה מזכירה סוגי קורבנות שונים:

קרבן עולה הוא קרבן שבו הקרבן כולו עולה לה’, ומהווה ביטוי לטהרת הכוונה של האדם, קרבן שהוא כולו “לשם שמים” (יש אומרים שהמילה הלועזית holocaust – הכינוי בלועזית לשואה, מקורה במילה העברית – ״עולה״, קרבן הנשרף כולו). לעומתו, קרבן השלמים מובא כשהאדם מעוניין לאכול את בשר הבהמה ורוצה לתת לאכילה זו מימד של קדושה. קרבן חטאת ואשם מובאים במקרה שהאדם הגיע למצב בו הוא חטא (בשגגה) או אשם, ומוצעת לו דרך תיקון.

בעל החיים שנבחר אינו מקרי אלא מבטא צד מסוים בנפש המקריב כדי שהמקריב רואה את עצמו בו: שור מבטא את הצג הגשמי-כלכלי כולל פריון (ולכן לא פעם נקרא גם פר, מלשון פרו ורבו). לעומת זאת, אדם הרוצה לבטא כניעה, מביא כבש שהולך אחרי הרועה כשראשו שפוף, כנוע בין כל הצאן, או אדם שרוצה לקרב את רגשותיו לקב״ה, מביא עז המבטא עזות, ועוד. לכל צעד בתהליך יש משמעות הלכתית, סמלית ורוחנית.

למשל, התפארת שמואל (רבי אהרן שמואל קאיידנובר 1614-1676, רב אשכנזי חשוב במרכז ומזרח אירופה) כתב על הפסוק: ״וְאִם־נֶ֧פֶשׁ אַחַ֛ת תֶּחֱטָ֥א בִשְׁגָגָ֖ה מֵעַ֣ם הָאָ֑רֶץ בַּ֠עֲשֹׂתָ֠הּ אַחַ֨ת מִמִּצְוֺ֧ת ה׳ אֲשֶׁ֥ר לֹא־תֵעָשֶׂ֖ינָה וְאָשֵֽׁם״ (ויקרא ד,כז)… ״כל דבר הנעקר משורשו, מקבל טומאה (טומאה היא קלקול ומרחק רוחני, לא לכלוך פיזי), וכשהוא מחובר לשורש, אינו מקבל טומאה. כך הדבר בגידולי קרקע, בזרעים ובנטיעות. כל זמן שלא קצצם, תלשם או קצרם, אינם מקבלים טומאה. וככה במים, אינם מקבלים טומאה אם הם מחוברים למעיינם. וכך הדבר באנשים: אם הם באחדות אחד עם השני, הטומאה לא שולטת בהם. אבל ״נפש אחת – תחטא״ – נפש בודדה ויחידה בלי קשר וחיבור עם העם, עלולה לבוא לידי עבירות״.

דוגמא נוספת היא הפסוק ״וְשָׁחַט֙ אֶת־הַ֣חַטָּ֔את בִּמְק֖וֹם הָעֹלָֽה״ (שם, כט) עליו אומר רבנו בחיי (רבי בחיי בן יוסף אבן פקודה 1050-1120, דיין ופילוסוף בסרגוסה שבספרד, מחבר הספר ״תורת חובות הלבבות״): ״טעם שחיטת החטאת במקום שחיטת העולה, כדי שלא יתבייש החוטא, ולא יבחינו בו בני אדם אם חטא בהרהור או במעשה״.

לא פעם כשמגיעים לספר ויקרא, אנחנו שומעים על הכהנים שחטאו ומעלו בתפקידם. ציטוטים נשלפים מדברי הנביאים שהזהירו מפני קרבנות חסרי משמעות ושחיתויות שונות שלצערנו, קרו, והכהונה והקורבנות מקבלים שם רע. כמי שזכתה בשם משפחה המעיד על קרבה כלשהי למוסד זה🙂 אולי אני משוחדת, אך אגיד מילה נוספת כאן: לפני שאנחנו שופטים מה היה, נזכור שבימים עברו, מוסד הכהונה התקיים לצד המלוכה והסנהדרין. ביחד שמרו על הפרדת רשויות והיוו גוף שלטון שלם שפעל למען חברה בריאה. בתקופת הגלות אחרי החורבן, הצטמצם העולם היהודי לביתו של היחיד ומשפחתו, אך עם המהפכה התעשייתית והחזרה לארץ, נפתחנו לשוב לבנות חברה רחבה ומתוקנת יותר. קל להבין, כמעט בכל מהדורת חדשות, שעוד לא הגענו אל המנוחה והנחלה, ועוד לא מצאנו את האיזון האופטימלי בין הרשויות, אבל זה בשום אופן לא מתיר לנו לבטל אחת מהן ולא מונע מאיתנו להמשיך לחלום, לשאוף ולכוון לשם. מי יתן ועוד נגיע.

שבת שלום.

Welcome to the Book fo Leviticus – Vayikra

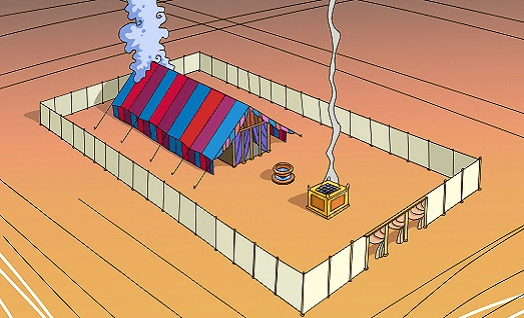

The Book of Leviticus, like the Book of Exodus, begins with the letter vav – which literally means “and” – continuing what we have heard so far: in the Book of Exodus, the Creator speaks to the created through miracles, the event at Mount Sinai and the Ten Commandments, and the construction of the Tabernacle that will give a place to the Divine Presence in this world, while the Book of Leviticus – as its name in Hebrew implies (Vayikra, literally “and he called”) the created (i.e. the human) is called to draw closer to the Holy One. Therefore, here the system of the sacrifices – avodat hakorbanot – is mentioned and renewed; korban from the root k.r.v., to be drawn closer.

Most of the sacrifices were from animals, and raise a question: How can sacrificing an animal bring a person closer to Gd? What’s the connection?? True, not every slaughter of an animal is a sacrifice, and where the strongest potential for closeness and purity is found, there also lies the possibility of exactly the opposite.

Let’s take a step back: the soul and the body, by way of a parable, are like a driver in a rented car. If we asked the driver – the soul – what it wants, it might say – to fly and immediately reach the desired destination, but because it’s dependent on the vehicle, that is, the body, it must move according to the vehicle’s speed and laws of motion. And the analogy? If we were to ask only the pure soul what it wants, it might tell us that it only wants to go back to be with the Creator.

That’s why it is said at the beginning of the book of Leviticus: “…when someone from among you brings an offering to Hashem”… if the human being – here called “Adam”- wants to make an “offering” – korban, to draw close, he might have offered his own self, but we have already learned from the Binding of Isaac, that even if a human-being is willing, Gd forbid, to give up his life, he should not, under no circumstances, do that. Rather, “you shall choose your offering from the herd or from the flock (the rest of the same verse in Leviticus 1:2). Gd wants us to choose life and it’s enough that we have the intention and willingness to give our lives. Then the animal will serve as a substitute.

We may ask further: “Rachmana Liba Bai” God wants the heart – and all that is needed is “intention,” then what is the purpose of an animal? What about “animal suffering”?

The answer to this is not always satisfactory, because we live in a very different world from the world in which the Torah was given and fully observed, but still, let’s try:

The Torah itself treats the taking of an animal’s life very carefully. In the beginning, in the Garden of Eden, all humans and animals were vegan-vegetarians. Eating meat came as a kind of compromise after the story of the flood and Noah’s Ark. Even when the Israelites were in the desert, there were words spoken against eating meat “just for the sake of it,” and by “just” we mean even as food, not to mention the laws of kashrut that further restrict the eating of meat. Whoever wanted to eat meat had to do so in holiness, and usually also share it with others (the sin offering – has to be shared with the priests, the Passover offering – with the family and/or a large group). I have no doubt that the amount of meat eaten was very small, given the many laws around it. On the contrary: today, there is much greater detachment, when all we have to do is go to the store, take some pink lump of something, put it in a sauce or on a fire, and not think about the fact that it was a living creature, breathing, licking grass for its own pleasure in the field.

The midrash wonders, if we could ask the animals, what would they say? In the haftarah for the Torah portion of “Ki Tisa“, we find the story of Elijah the prophet who chose to sacrifice two bulls in his struggle against the Ba’al prophets. Elijah’s bull followed him, but the bull that was brought to the Ba’al strongly objected. When the bull was asked why, it said that it did not want to go up on the altar in order to anger the Creator! In other words, it was bad enough to go up as a sacrifice, but at least for a noble cause and not for nonsense?! This is something that comes up today too – sacrificing a life for a noble cause is considered preferable to sacrificing a life “for nothing.” Similarly, only when Elijah promised the second bull that the name of the Holy One would be sanctified by it too, did he agree to go.

The Torah mentions different types of sacrifices:

A burnt offering (Ola) is a sacrifice in which the entire sacrifice is offered to Gd, and is an expression of the purity of the person’s intention, a sacrifice that is entirely “for the sake of Heaven” (some say that the word holocaust comes from this ola, a sacrifice that is completely burned). In contrast, the peace offering (shlamim) is offered when the person wants to eat the meat of the animal and wants to give this eating a dimension of holiness. A sin offering (chatat) and a guilt offering (asham) are offered in the event that a person has reached a state in which he has sinned (by mistake) or is guilty, and a way of correction is offered.

The animal chosen is not accidental but expresses a certain side of the soul of the sacrificer so that the sacrificer can see himself in it: an ox expresses the physical-economic aspect including fertility (which is why it is often also called par related to pru u’rvu – be fruitful and multiply). On the other hand, a person who wants to express submission brings a sheep that follows the shepherd with its head bowed, submissive among all the flock, or a person who wants to bring his feelings closer to Gd may bring a goat (ez) that expresses strength (azut), and more. Each step in the process has a halakhic, symbolic, and spiritual significance.

For example, the Tif’eret Shmuel (Rabbi Aharon Shmuel Kaidnover 1614-1676, an important Ashkenazi rabbi in Central and Eastern Europe) wrote about the verse: “And if a soul mistakenly sins from among the people of the land by doing one of the commandments of Hashem, which should not be done, and he’s guilty” (Leviticus 4:27)… Anything that is uprooted from its source becomes unclean (“uncleanness” – tum’a – is spiritual corruption and distance, not physical), and when it is attached to the root, it does not become unclean. The same is true of crops, seeds, and plantings. As long as they are not cut, pruned, or harvested, they do not become unclean. And so it is with water, they do not receive impurity if they are connected to their source. And so it is with people: if they are in unity with each other, impurity does not control them. But “a soul – will sin” – a lonely soul without connection and relationship with people, is liable to commit transgressions.”

“Another example is the verse “And the sin offering shall be slaughtered in the place of the burnt offering” (ibid., 29), about which Rabenu Bachye (Rabbi Bachye ben Yosef Ibn Pekuda 1050-1120, judge and philosopher in Saragossa, Spain, author of the book “Torat Chovt Halevavot”): “The reason for slaughtering the sin offering in the place of the burnt offering is so that the sinner will not be ashamed, and people will not notice him if he sinned in thought or in deed.”

Often, when we come to the book of Leviticus, we hear about priests who sinned and misused their role. Quotes are brought from the prophets who warned against meaningless sacrifices and various corruptions that unfortunately happened, and the priesthood and the sacrifices get a bad rap. As someone who has a family name that indicates some kind of connection to this institution 🙂 Maybe I’m biased, but I’ll add another word here: Before we judge what happened, let’s remember that in the past, the institution of the priesthood existed alongside the kingship and the Sanhedrin. Together they maintained the separation of powers, and formed a complete governing body that worked for a healthy society. During the time of exile after the destruction of the Temple, the Jewish person’s world shrank to one’s home and family’ but with the industrial revolution and the return to the Land, we have the opportunity to once again build a broader and more corrected society. It’s easy, from every news report, that we have not reached peace and quiet, and we have not yet found the optimal balance between the various governance parts. But that in no way allows us to cancel one of them and does not prevent us from continuing to dream, inspire and aim there, hoping one day we’ll make it.

Shabbat Shalom.