פרשת בשלח: ״וַיּוֹרֵ֤הוּ… עֵ֔ץ״…

פרשת ״בשלח״ נפתחת עם היציאה, סופסוף, ממצרים. נשאר רק עוד דבר אחד לעשות:

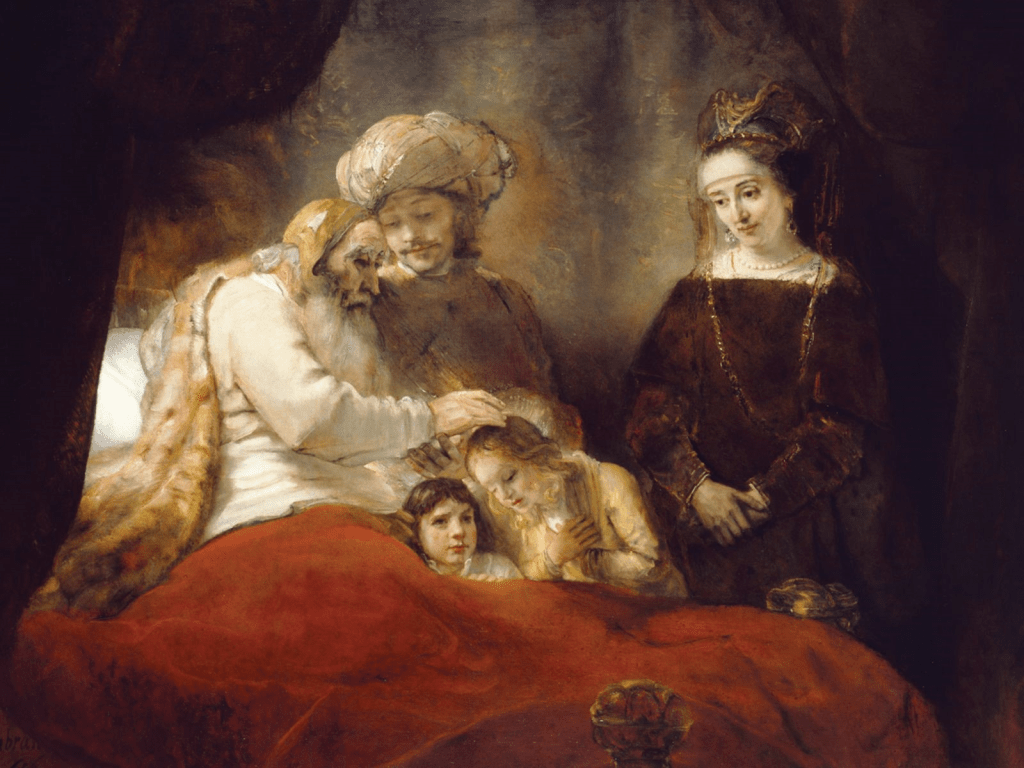

״וַיִּקַּ֥ח מֹשֶׁ֛ה אֶת־עַצְמ֥וֹת יוֹסֵ֖ף עִמּ֑וֹ כִּי֩ הַשְׁבֵּ֨עַ הִשְׁבִּ֜יעַ אֶת־בְּנֵ֤י יִשְׂרָאֵל֙ לֵאמֹ֔ר פָּקֹ֨ד יִפְקֹ֤ד אֱלֹהִים֙ אֶתְכֶ֔ם וְהַעֲלִיתֶ֧ם אֶת־עַצְמֹתַ֛י מִזֶּ֖ה אִתְּכֶֽם״ (שמות יג,יט), וכמה מצמרר לקרוא את השורות האלה דווקא בשבוע זה!

יוסף השביע את בני ישראל לפני שנפטר בשבועה כפולה: קודם כל, הקב״ה יוציא אתכם מכאן, וכשזה יקרה, בבקשה, קחו אותי אתכם הביתה. אלא שגם המצרים ידעו על השבועה, ומכיון שידעו שבני ישראל לא יצאו ממצרים בלי יוסף, השליכו החרטומים והאשפים את ארונו של יוסף בארגז מתכת כבד ואטום בנהר כדי שאיש לא יוכל למצוא אותו ובטח שלא להעלות אותו. משה חיפש אותו ימים ארוכים, והמצרים בטח גיחכו למראה ״עקשנותו״ ה״טפשית״.

אלא, שסוד מיקומו ארונו של יוסף נמסר לשרח בת אשר ש״נשתיירה מאותו הדור, והיא הראתה את המקום למשה. ״מיד עמד משה על שפת הנחל ואמר: יוסף, יוסף, אתה ידעת היאך נשבעת לישראל… בקש רחמים לפני בוראך ועלה מן התהומות! מיד התחיל ארונו של יוסף מפעפע ועולה מן התהומות בקנה אחד״… (דברים רבה יא,ז). רש״י מוסיף שלא רק את עצמות יוסף העלו אז אלא ״אף עצמות כל השבטים (אחיו) העלו עמהם, שנאמר ״אתכם״.

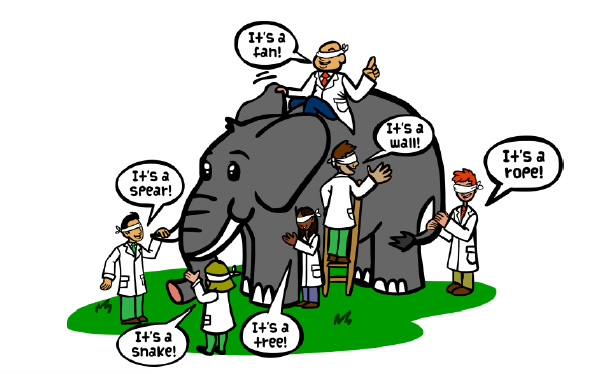

אך מה פירוש ״עצמות יוסף״?

אבן עזרא מסביר בדרכו שאחרי כל השנים במצרים, זה כל מה שנשאר מהגוף, אפילו אם המצרים חנטו את יוסף כפי שמסופר, אבל פרשנים חסידיים יותר מחברים בין ״עצם״ במובן הפיזי ל״עצמיות״ הפנימית. למרות כל כישוריו והנהגתו של משה, למשה לא היה כל מה שאנחנו צריכים כדי להיות לעם, לקבל את התורה ולהגיע לארץ. באופן סמלי, הוא נזקק לחלקים בעם ישראל שלא היו לו, והיו ליוסף, כמעט ההיפך הגמור ממנו. כמה יכל להיות ״נח״ לוותר! אך משה יודע שבלעדי כל החלקים השונים, אי אפשר יהיה להמשיך.

הרש״ר הירש מסביר שהשורש ע.צ.ם שמתחיל במילה ״עץ״ עוסק בצבירת כוח פנימי. הוא מחבר אותנו מכאן לשורשים אחרים שמתחילים באותן האותיות: למשל, ע.צ.ב – ״לצבור״ צער בפנים. ע.צ.ה – לרכז אנרגיה ו/או חוכמה לעשות טוב, ואפילו ע.צ.ל – מחזיק את האנרגיה שלו בפנים, רחוקה אפילו מעצמו.

מה שלוקח אותנו הלאה לתוך הפרשה…

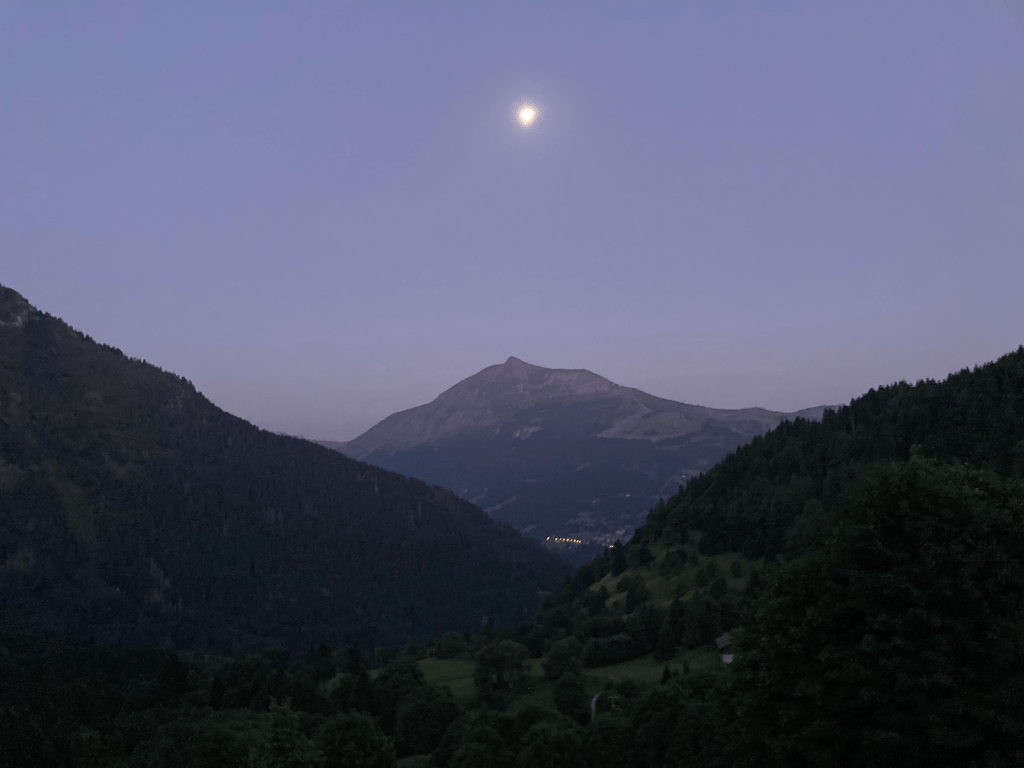

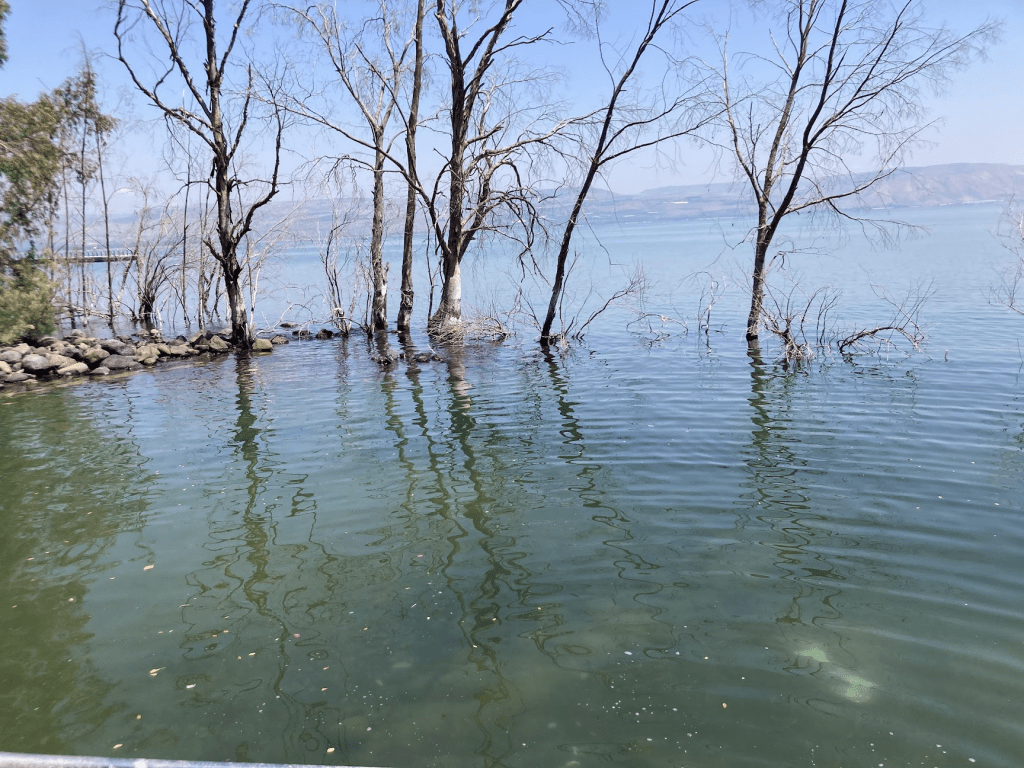

אחרי היציאה המופלאת לחירות, מתחילים החיים ה״אמיתיים״, והנה, ״וְלֹא יָכְלוּ לִשְׁתֹּת מַיִם מִמָּרָה כִּי מָרִים הֵם; עַל כֵּן קָרָא שְׁמָהּ מָרָה (מלשון “מר”). וַיִּלֹּנוּ הָעָם עַל מֹשֶׁה לֵּאמֹר: מַה נִּשְׁתֶּה? וַיִּצְעַק אֶל ה’, וַיּוֹרֵהוּ ה’ עֵץ; וַיַּשְׁלֵךְ אֶל הַמַּיִם וַיִּמְתְּקוּ הַמָּיִם״ (שמות טו,כב-כו).

למקרה שאנחנו חושבים ש״הם תמיד מתלוננים״, מספרת לנו התורה ששלושה ימים (!) הלכו בני ישראל במדבר ללא מים, שזה נס בפני עצמו (בוא נראה אותנו, אפילו רק 3 שעות…). לאחר שלושה ימים הגיעו למקום עם מים, איזה יופי, אך ככל שהשמחה גדולה, כך גם האכזבה. בני ישראל ממלאים את כליהם, מצפים ללגימה המתוקה הראשונה לאחר ימים של הליכה בחום ובצמא, אך מגלים שטעם המים מר כלענה! אוי, מה עושים?

אולי משה היה יכול לומר: “נו באמת, אז המים קצת מרים, כן, החיים הם לא פיקניק, ככה זה, מה אני יכול לעשות״… או לחלופין, להאשים אותם: “למה אתם שוב מתלוננים…” ואף לדרוש: “מים מרים זה טוב לכם! זה בונה אופי! תלמדו להגיד תודה!”… אך במקום זאת, ה’ מורה למשה להשליך עץ אל המים, והמים המרים נעשים מתוקים.

חז״ל מסכימים שהעץ שהושלך היה עץ מר. ע״פ המדרש, משה חשב שהקב״ה יאמר לו להשליך מעט דבש או תאנה מיובשת (מתוקה) וכך ימתקו המים. אך אמר לו הקב״ה: “משה, דרכיי שונות מדרכיך. עתה עליך ללמוד, שכן נאמר ‘ויורהו’, לא ‘ויראהו’, אלא ‘ויורהו’ מלשון הוראה ולימוד: ללמד את משה – ואותנו – את דרכי ה’”. (מדרש תנחומא).

מתברר שאין כאן רק צורך להמתיק את המים (שהרי המים יכלו להיות מתוקים מלכתחילה!), אלא גם הזדמנות. אם נקרא שוב את הפסוק “כי מרים הם”, נראה שאפשר להבין ש“הם” יכול להתייחס לבני ישראל עצמם! כלומר, בני ישראל לא יכלו לשתות את המים, משום שהם עצמם – בני ישראל – היו מרים.

בסיפור שלנו, אז וגם היום, יש אתגרים רבים. חלקם לא תלויים בנו אך חלקם לגמרי שלנו. מסתבר שאי אפשר באמת לצאת אל החירות בלי עבודה פנימית עקבית ומסורה שתשחרר אותנו מן המרירות שבתוכנו.

שבת שלום וטו בשבט שמח

Parashat B’shalach: “And Hashem showed him a tree”

Parashat B’shalach opens with the long-awaited departure from Egypt. There is only one more thing left to do:

“And Moses took the bones of Joseph with him, for he had made the children of Israel solemnly swear, saying, ‘God will surely remember you, and you shall bring up my bones from here with you’” (Exodus 13:19).

How chilling it is to read these verses דווקא this week!

Before his death, Joseph bound the Children of Israel with a double oath: first, that the Holy One, blessed be He, would indeed take them out of Egypt; and when that happened, they were to take him with them back home. But the Egyptians also knew of this oath, and since they understood that the Children of Israel would not leave Egypt without Joseph, their magicians and sorcerers cast Joseph’s coffin into the Nile, sealing it inside a heavy, watertight metal chest so that no one could ever find it, let alone not raise it up. Moses searched for it for many days, while the Egyptians surely snickered at what they saw as his “foolish” stubbornness.

However, the secret of Joseph’s coffin’s location was passed on to Serach bat Asher, “who had survived from that generation,” and she showed Moses the place. “Immediately Moses stood at the bank of the river and said: ‘Joseph, Joseph! You know how you made Israel swear… plead for mercy before your Creator and rise up from the depths!’ Immediately, Joseph’s coffin began to bubble and emerge from the depths, straight upward” (Devarim Rabbah 11:7).

Rashi adds that it was not only Joseph’s bones that were brought up then, but “also the bones of all the tribes (his brothers), as it says: ‘with you.’”

But what does “the bones of Joseph” really mean?

Ibn Ezra explains in his characteristic way that after so many years in Egypt, this was all that remained of the body—even if, as the Torah relates, the Egyptians embalmed Joseph. But more Hasidic commentators connect the word etzem (bone) in its physical sense with atzmiut—one’s inner essence. Despite all of Moses’ abilities and leadership, Moses did not possess everything needed to become a People, to receive the Torah, and to reach the Land. Symbolically, he needed elements within the people of Israel that he himself did not have, but which Joseph, almost his complete opposite, did. How tempting it might have been to “give up”! Yet Moses understood that without all the different parts of the People, it would be impossible to move forward.

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch explains that the root ע.צ.ם, which begins with the word etz (tree), deals with the accumulation of inner strength. From here he connects us to other roots that begin with the same letters: for example, ע.צ.ב—accumulating pain inwardly; ע.צ.ה—focusing energy and/or wisdom in order to do good; and even ע.צ.ל—holding one’s energy inside, distant even from oneself (and in Hebrew meaning – lazy).

Which all leads us further into the parashah…

After the miraculous departure to freedom, “real life” begins. And then:

“They came to Marah, but they could not drink the water of Marah because it was bitter; therefore it was called Marah (‘bitter’). And the people complained against Moses, saying, ‘What shall we drink?’ Moses cried out to Hashem, and Hashem directed him to a tree; he threw it into the water, and the water became sweet” (Exodus 15:22–25).

In case we are tempted to think, “they’re always complaining,” the Torah tells us that the Children of Israel walked for three (!) days in the desert without water (let’s try for 3 hours…); that in itself was a miracle. After three days they reached a place with water, how wonderful! But the greater the joy, the greater the disappointment. The Children of Israel filled their vessels, anticipating the first sweet sip after days of walking in heat and thirst, only to discover that the water tasted bitter as wormwood. Oh no, now what?

Perhaps Moses could have said: “Come on, so the water is a bit bitter; yes, life just isn’t a picnic, that’s how it is, what can I do?” Or alternatively, blamed them: “Why are you complaining again…?” Or even preached: “Bitter water is good for you! It builds character! Learn to be thankful!”

But instead, Gd instructs Moses to throw a tree into the water, and the bitter water becomes sweet.

Our sages agree that the tree that was thrown in was itself a bitter tree. According to the Midrash, Moses thought that the Holy One, blessed be He, would tell him to throw in some honey or a (sweet) dried fig, and thus sweeten the water. But Gd said to him: “Moses, My ways are different from yours. Now you must learn, for it says ‘He directed him’ (vayorehu): not ‘He showed him’ (vayarehu), but ‘He directed him’ – from the language of instruction and teaching: to teach Moses, and us, the ways of Gd” (Midrash Tanchuma).

It turns out that this is not only about sweetening the water (after all, the water could have been sweet from the outset!), but also about an opportunity. If we reread the verse, “for they were bitter,” we can understand that “they” might refer to the Children of Israel themselves. That is, the Children of Israel could not drink the water because they themselves (the Children of Israel) were bitter.

In our story, then and now, there are many challenges. Some do not depend on us, but some are entirely ours. It seems that it is impossible truly to go out to freedom without consistent, dedicated inner work that will free us from the bitterness within.

Shabbat Shalom & a happy Tu-Bishvat!

There can be miracles from the “everlasting” Prince of Egypt – should have been here but didn’t load 🙂 enjoy on your own!