והיה “כי תבוא” אל הארץ היום…

פרשת ״כי תבוא״ פותחת במילה “והיה”, וחז”ל אומרים ש״והיה – לשון שמחה״, לעומת ״ויהי״ שתמיד מצביע על צער או אסון מתקרב. לכאורה, יש כאן ״טריק״ ידוע בעברית תנכית: את הטיית הפועל בעבר אפשר יחד עם ״וו ההיפוך״ להפוך מעבר לעתיד. כך, ״והיה״ נהיה במשמעותו ל-יהיה.

אבל הטכניקה הדקדוקית אינה רק טכניקה אלא דרך לבטא את האפשרות שלנו להפוך את העבר לעתיד. בעבר, יש יסודות, שורשים, היסטוריה, מאין באנו, כל מה שמהווה את הבסיס להיותנו מי שאנחנו. אלו יכולים להוות משקולות כבדים מאד, גם ברמה אישית וגם ברמה הלאומית. אבל הם יכולים להיות גם כלים למינוף שמתוכם נבנה חזון ותקווה. כך הם יהפכו ממשקולת כבדה שעלולה לגרור אותנו למטה, לכלי לטיפוס שמושך אותנו מעלה, ויעזרו לנו ליצור עתיד טוב עוד יותר.

הכניסה לארץ מלווה באתגרים רבים, סכנות ואויבים מחוץ וגם מפנים. הסכנה הגדולה ביותר, ע״פ התורה, איננה אויב, אכזר ככל שיהיה, או מישהו מבני ישראל שלא חושב בדיוק כמוני. הסכנה הגדולה ביותר היא שניקח את הכל כמובן מאליו, נשתקע ו”נשקע”. אחת התרופות לכך היא מצוות הביכורים. התיאור כל כך יפה: עלינו לקחת את הטנא עם הפרי הראשון שגדל בשדנו, וללכת לכהן ״אשר יהיה בימים ההם״. אפשר לראות את החקלאי ב״סלנו על כתפנו״, צועד לו בנחת בשבילי הארץ לבית המקדש…

אך הביכורים הציבו אתגר עצום, שעומד במיוחד בניגוד לחיינו אנו. בימינו, החיים הפכו למאד מהירים. כמו שיש לנו ״פאסט פוד״, אוכל מהיר, הכל צריך להיות ״כאן״ ו״עכשיו״, מייד או אפילו. הביכורים עבדו לפי שעון אחר לגמרי.

שנים של חריש, זריעה, שתילה, טיפול וטיפוח… ואז, הנה, עכשיו התאנה הראשונה כאן! אנחנו רוצים לתת ביס גדול בפרי העסיסי והטעים! באה תורה ואומרת, רגע. הנה, נקשור על התאנה הזו סרט מיוחד, נשמור עליה יפה, נוודא שהיא ממשיכה להבשיל ואז נקטוף אותה, נעטוף בזהירות, נשים בסל ונצא לנו לירושלים בתפילה ששום דבר בטנא לא יתקלקל, וגם בתפילה, שהשדות שהשארנו בבית – לא יפגעו. ושם, בבית המקדש, אתה אומר לכהן, ואת האמירה הזו רש״י מפרש ש״שאינך כפוי טובה״. בפסוקים אנחנו אומרים משהו כמו, ׳הנה פרי השותפות שלי עם המתנות הנפלאות שהקב”ה העניק לי ולמשפחתי. יפה, נכון? קחו לכם אותה, תודה רבה׳. ואז חוזרים הביתה בידיים ריקות ולב מלא שמחה, כי בתוך כל ים האתגרים סביבנו, גם שמחה היא מצווה, והעונשים שיתוארו בהמשך נאמר שיגיעו ״תַּ֗חַת אֲשֶׁ֤ר לֹא־עָבַ֙דְתָּ֙ אֶת־יְהֹוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֔יךָ בְּשִׂמְחָ֖ה וּבְט֣וּב לֵבָ֑ב מֵרֹ֖ב כֹּֽל״ (דברים כח,מז). מסתבר שלא מספיק רק לעשות, צריך גם שנעשה משמחה, בלי הפרצוף החמוץ הזה שעושה טובה… ושוב נשאל, אפשר לצוות על שמחה? הרי אי אפשר ״להכריח״ מישהו להיות שמח… אבל אולי כי התורה חשבה ששמחה זה לא רק מה שקורה לנו מחוץ, אלא גם החלטה אישית, לאומית, מושכלת, לבחור לראות את הטוב.

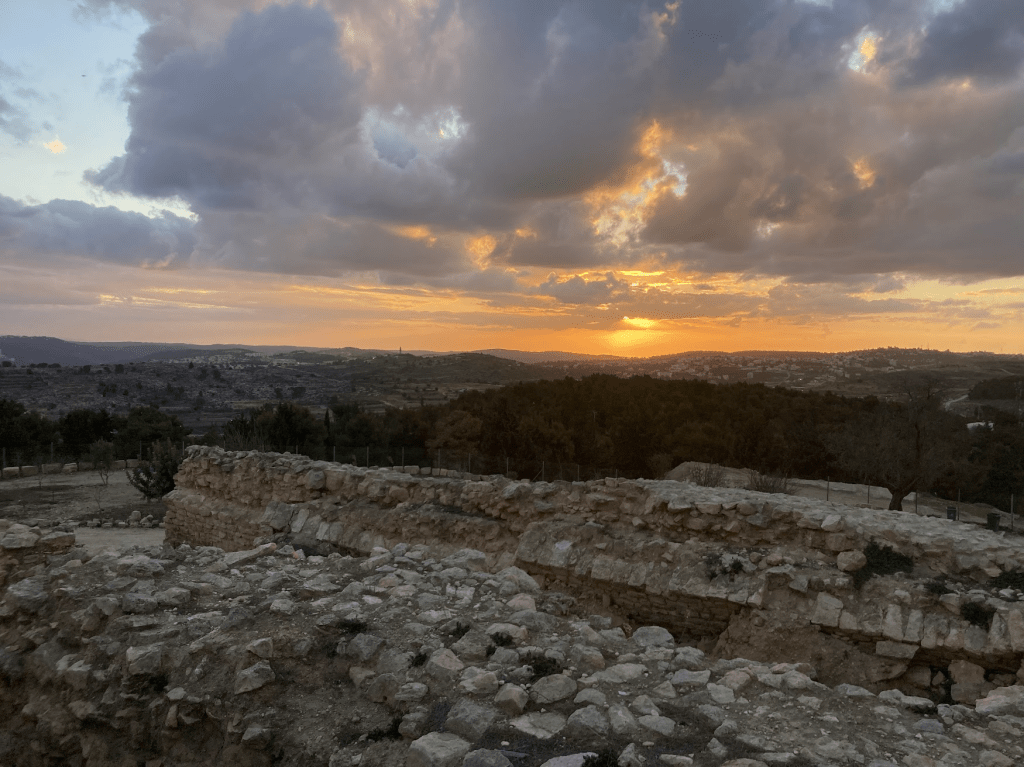

מעניין שהאדם שמביא את הביכורים, אומר, בין השאר, לכהן: “הגדתי היום… כי באתי אל הארץ“… התיאור ״באתי אל הארץ״ התאים רק לדור של יהושע. אח״כ עם ישראל ישב בארצו. לא היתה קליטת עליה, לפחות עד לחורבן בית ראשון… למה להכניס כאן פסוק לטקסט שלא יהיה רלוונטי במשך מאות שנים? יתכן שהתורה רצתה שהתחושה שלנו תהיה של ׳היום, באתי את הארץ׳. היום, ביום זה ממש. כל יום. לפתוח חלון ולהגיד – וואו! בלי אבל… אח״כ. להתרגש ולהרגיש את ההתחדשות של המקום הזה, לדעת שלהגיע לכאן לא שייך רק לדורות הקודמים, ושזו רק ההתחלה.

בסוף הפרשה, אחרי הברכות ו-98 קללות (!), משה אומר את אחד הפסוקים האהובים עלי: “וְלֹא־נָתַן֩ ה’ לָכֶ֥ם לֵב֙ לָדַ֔עַת וְעֵינַ֥יִם לִרְא֖וֹת וְאׇזְנַ֣יִם לִשְׁמֹ֑עַ עַ֖ד הַיּ֥וֹם הַזֶּֽה” (כט:ג). עד היום הזה?! 40 שנה אחרי צאתם ממצרים, רק עכשיו הם מתחילים להבין מה הייתה יציאת מצרים ומה כל המסע הזה? אמרה הגמרא: ״מכאן למדו חכמינו שאין אדם עומד על דעת רבו עד ארבעים שנה״ (עבודה זרה ה:א), כלומר, למרות הרצון להבין את ההווה מיידית (ועוד יותר, ״להסביר״ אותו שוב ושוב…), זהו דבר בלתי אפשרי, חסר תועלת ולפעמים גם מזיק. יש דברים שצריך לעשות ולחוש ״היום״, אבל צריך גם לזכור שאנחנו עם שחי על שעון אחר, ויש דברים שצריכים זמן. ופרספקטיבה. ונשימה. עמוקה. מאד.

שבת שלום.

“And it shall be when you come into the Land today…”

Parashat Ki Tavo opens with the word “Vehaya” (“And it shall be”), and the Sages say that “Vehaya” always implies joy, in contrast to “Vayehi” which signals sorrow or an impending disaster. At first glance, this seems like a well-known “trick” in Biblical Hebrew: a past tense verb can be flipped into the future using the “vav conversive”. “Haya” means – was; “Vehaya” actually means “It shall be.”

But this grammatical technique is more than just a technicality — it’s a way to express our ability to transform the past into the future. The past contains foundations, roots, history, our origins, everything that forms the basis of who we are. These can be heavy weights, both personally and nationally. But they can also be tools of leverage — which we can use to build vision and hope. In this way, they can become not burdens that drag us down, but stepping stones that pull us upward and help us shape a better future.

Entering the Land comes with many challenges — dangers and enemies from outside and within. But according to the Torah, the greatest danger is not some cruel enemy, nor is it a fellow Israelite who doesn’t think exactly like I do. The greatest danger is taking it all for granted, becoming complacent and indifferent.

One of the remedies for this is the mitzvah of Bikkurim (the offering of first fruits). The description is so beautiful: we are to take a basket filled with the first fruits that grew in our field and bring it to the kohen “who will be in those days.” You can almost see the farmer in your imagination, carrying the basket on his shoulder, walking peacefully along the paths of the Land toward the Temple…

But Bikkurim presented a huge challenge, especially when contrasted with our modern way of life. Today, everything is fast. Just like we have “fast food,” we expect everything to be “here” and “now,” instantly or even sooner. But the mitzvah of Bikkurim operated on a completely different clock.

Years of plowing, sowing, planting, nurturing… and then, finally, the first fig appears! Our natural instinct is to take a big bite of that juicy, delicious fruit! But the Torah says — wait. Tie a special ribbon around that fig, watch over it, make sure it keeps ripening, then gently pick it, carefully wrap it, place it in a basket, and set out for Jerusalem — praying that nothing in the basket spoils, and also praying that nothing harms the fields we’ve left behind. And there, in the Temple, we recite a passage that essentially says: Here is the fruit of my partnership with the wondrous gifts that God has given me and my family. It’s beautiful, right? Take it, thank you very much. And then — we return home, empty-handed but with hearts full of joy. Because in the midst of all the challenges around us, joy is also a mitzvah. And the punishments listed later in the parashah are said to come “because you did not serve the Lord your God with joy and a good heart out of the abundance of all things” (Deuteronomy 28:47).

It turns out that it’s not enough just to do the right thing — we also have to do it with joy, not with that sour face that makes it look like we’re doing the world a favor… And again we ask — can one be commanded to be happy? After all, you can’t force someone to be joyful… But maybe the Torah’s perspective is that joy isn’t only a reaction to what happens to us externally, but also an intentional, national, thoughtful decision to see the good.

It’s interesting that the person bringing the first fruits says to the priest: “I declare today… that I have come to the Land…” The phrase “I have come to the Land today” only really made sense for the generation of Joshua. After that, the people of Israel were already settled in the Land. There was no mass aliya — at least not until after the destruction of the First Temple. So why include a verse that wouldn’t be relevant for hundreds of years?

Perhaps the Torah wants us to feel as if “Today, I have come to the Land.” Today — this very day. Every day. To open the window and say, Wow! with no “but…” afterwards; to be moved and feel the renewal of this place; to understand that arriving here, in the Land, isn’t something that only belonged to earlier generations — it’s just the beginning.

At the end of the Torah portion, Moses says one of my favorite verses:

“And the Lord has not given you a heart to know, eyes to see, or ears to hear — until this day.” (Deut. 29:3)

Until this day?! Forty years after leaving Egypt, only now they are beginning to understand what the Exodus from Egypt was really about and what this whole journey meant?

The Talmud says: “From here our sages learned: a person does not fully grasp the mind of their teacher until forty years have passed” (Avodah Zarah 5a). In other words, as much as we want to understand the present moment instantly (and even more — to explain it over and over…), it’s actually impossible, unhelpful, and can be even harmful.

There are things that must be felt and acted upon today, but we also need to remember, that we are a People who live by a different clock. Some things just need time. And perspective. And a deep, deep breath.

Shabbat Shalom.

Arise, shine, for your light has dawned;

The Presence of GOD has shone upon you! (Isaiah 60,1)

יפה כתבת. כשהמילה “ויהי” חוזרת על עצמה בפרשת בראשית (ויהי אור וכו’) היא מצביעה על צער?

הי, הערה מצוינת!הדברים מבוססים על הגמרא במסכת מגילה, דף י, עמוד ב. כתוב:אָמַר רַבִּי לֵוִי וְאִיתֵּימָא רַבִּי יוֹנָתָן: דָּבָר זֶה מָסוֹרֶת בְּיָדֵינוּ מֵאַנְשֵׁי כְּנֶסֶת הַגְּדוֹלָה, כׇּל מָקוֹם שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר ״וַיְהִי״ אֵינוֹ אֶלָּא לְשׁוֹן צַעַר.בהמשך מובאת דעה שניה. כתוב:אָמַר רַב אָשֵׁי: כׇּל ״וַיְהִי״ — אִיכָּא הָכִי וְאִיכָּא הָכִי, ״וַיְהִי בִּימֵי״ — אֵינוֹ אֶלָּא לְשׁוֹן צַעַר. כלומר, אם כתוב רק ״ויהי״, זה יכול להיות גם צער, גם שמחה, אבל ״ויהי בימי״ – זה תמיד צער. כמו לכל כלל, יש יוצאים מן הכלל.למשל, ויהי ביום השמיני… ויהי מקץ..השאלה של בריאת העולם מעניינת: האם זה היה אירוע ״שמח״ או אירוע של ״שבירה״?אני חושבת שטוב להשאר עם שאלה -שבת שלום ותודה רבה

תודה על ההסבר המפורט. מעניין