פרשת וירא – עקדת יצחק

PODCAST WITH Or Yochai Taylor ON VAYERA: https://open.spotify.com/episode/0J2EvEsPpgM5NidV28RGRN

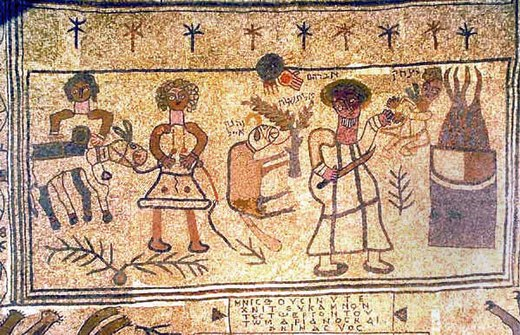

קשה לנו לקרוא את הפרק על עקדת יצחק, במיוחד בעיניים של ימינו המודרניים והעכשוויים. אני מודה: לא בלב קל הסעתי את בני לשער בסיס המילואים ב-7.10.2023, מקוה שעד שנגיע, הכל יתברר כטעות ונחזור הביתה… חושבת על כל המלחמות שחוויתי כאן, שעברה משפחתי, ובאף אחת מהן לא הייתי אמא לחייל… חושבת על אברהם אבינו, ותוהה, איך יתכן שהאיש שכל חייו מסמל חסד, שמתווכח עם אלוהים שלא ישמיד עיר מלאת חטאים וחוטאים, מתמקח ומנסה בכל כוחו להציל עוד אחד ועוד אחד, אולי 50 אולי 45…, בכזו קלות נענה לצו האל שאמר לו: ״קַח־נָ֠א אֶת־בִּנְךָ֨ אֶת־יְחִֽידְךָ֤ אֲשֶׁר־אָהַ֙בְתָּ֙ אֶת־יִצְחָ֔ק וְלֶ֨ךְ־לְךָ֔ אֶל־אֶ֖רֶץ הַמֹּרִיָּ֑ה וְהַעֲלֵ֤הוּ שָׁם֙ לְעֹלָ֔ה עַ֚ל אַחַ֣ד הֶֽהָרִ֔ים אֲשֶׁ֖ר אֹמַ֥ר אֵלֶֽיךָ״ (בראשית כב,ב)?

ואיך מייד, ״וַיַּשְׁכֵּ֨ם אַבְרָהָ֜ם בַּבֹּ֗קֶר, וַֽיַּחֲבֹשׁ֙ אֶת־חֲמֹר֔וֹ, וַיִּקַּ֞ח אֶת־שְׁנֵ֤י נְעָרָיו֙ אִתּ֔וֹ וְאֵ֖ת יִצְחָ֣ק בְּנ֑וֹ וַיְבַקַּע֙ עֲצֵ֣י עֹלָ֔ה וַיָּ֣קׇם וַיֵּ֔לֶךְ אֶל־הַמָּק֖וֹם אֲשֶׁר־אָֽמַר־ל֥וֹ הָאֱלֹהִֽים״ (שם,ג). כמה פעלים (6) וכמה פעילות בפסוק אחד! אברהם קם בבקר… איך הוא בכלל יכול לישון לפני בקר שכזה? ולא רק ״קם״, אלא משכים למצווה! בעצמו הוא חובש את חמורו, למרות שיש לו נערים ועוזרים סביבו. הוא לוקח את נעריו ואת יצחק. הוא מכין את עצי העולה, מלאכה שגם היא ככל הנראה לא קלה פיזית, והוא קם והולך…

ככל הנראה אברהם כאן בן 137 שנה כאן. יצחק, בניגוד לכל כך הרבה ספרי תורה מיוצרים לילדים, איננו ילד שהאיש הזקן גורר אחריו במעלה ההר, אלא איש צעיר וחזק, כבן 37 שנה, שהולך עם אביו על דעתו.

יצחק לא פעם מתואר כאיש פסיבי, הילד של אמא שלו. הכל צריך לעשות בשבילו, אפילו כלה נצטרך להביא לו כי לבד, הוא לא עושה ״שום דבר״, אבל, שלא נטעה בו. ה״פסיביות״ שלו היא איננה ישנוניות וחוסר עשיה, אלא דין וגבורה, כמו סלע שעומד על מקומו, לא מתוך חולשה אלא מתוך כוח ועוצמה.

ובפרק הזה, שני הכוחות האלה, אברהם, איש החסד, ויצחק, איש הגבורה, הולכים ״יחדיו״ לברור משלהם. האם אחד עדיף? השני? ואולי שניהם? איך?

בפרק הקודם אמרה שרה לאברהם: ״גָּרֵ֛שׁ הָאָמָ֥ה הַזֹּ֖את וְאֶת־בְּנָ֑הּ כִּ֣י לֹ֤א יִירַשׁ֙ בֶּן־הָאָמָ֣ה הַזֹּ֔את עִם־בְּנִ֖י עִם־יִצְחָֽק״ (בראשית כא,י). נשים לב לשייכויות של הילדים: היא קוראת לישמעאל – ״בנה״ של האמה, ולא בנו של אברהם, ובהחלט לא בנם, שלא יירש עם ״בני, עם יצחק״. ובפסוק הבא? ״וַיֵּ֧רַע הַדָּבָ֛ר מְאֹ֖ד בְּעֵינֵ֣י אַבְרָהָ֑ם עַ֖ל אוֹדֹ֥ת בְּנֽוֹ״ (שם,יא). בנו… ויש על כך פירושים שונים אבל איש לא מערער על כך שהכוונה לישמעאל, ״בנו״ של אברהם, לעומת יצחק שהוא ״בנה״ של שרה.

ואז מגיעה העקדה. ואברהם לוקח את יצחק ״בנו״, והנה, בעודם הולכים, יצחק פונה אל אברהם ״אָבִיו֙, וַיֹּ֣אמֶר, ׳אָבִ֔י׳, וַיֹּ֖אמֶר, ׳הִנֶּ֣נִּֽי בְנִ֑י׳, וַיֹּ֗אמֶר, ׳הִנֵּ֤ה הָאֵשׁ֙ וְהָ֣עֵצִ֔ים וְאַיֵּ֥ה הַשֶּׂ֖ה לְעֹלָֽה׳?

וַיֹּ֙אמֶר֙ אַבְרָהָ֔ם: ׳אֱלֹהִ֞ים יִרְאֶה־לּ֥וֹ הַשֶּׂ֛ה לְעֹלָ֖ה בְּנִ֑י׳, וַיֵּלְכ֥וּ שְׁנֵיהֶ֖ם יַחְדָּֽו (בראשית כב,ז-ח).

בפעם הראשונה בתורה, יצחק (כבר בן 37!) פונה לאביו בדיבור ישיר, ובפעם הראשונה, אברהם עונה לו בהתכווננות גמורה, ״הנני בני״. יצחק שואל את שאלתו, ואברהם עונה לו תשובה שאפשר להבין בשתי דרכים (לפחות): ״אלוהים יראה לו השה לעולה (פסיק) בני״ או גם ״אלוהים יראה לו השה (פסיק) לעולה בני״. כך או כך, יש ביניהם הבנה עמוקה, שלכל אחד מהם יש תפקיד, שונה לחלוטין מתפקידו ומקריאתו של השני. אברהם – איש החסד, ויצחק – איש הדין והגבורה. היינו חושבים שאם ״יסתדרו״ רק אם יהיו זהים, דומים, מסכימים על הכל? אברהם התלהב מישמעאל, הילד אותו לימד אמונה באל אחד, חסד ללא מעצורים, אבל הדברים האלו לבדם, בלי אותם מעצורים, שומשו – ועדיין משמים לרעה. נראה שדווקא כאן, דווקא בפרק המאתגר הזה, הם מבינים שהשוני ביניהם הוא מה שיבנה את דרך החיים הזו, ואולי, לראשונה, ההבנה הזו מאפשרת להם ללכת ״שניהם יחדו״, למלא ולקיים את מה שאמר אברהם קודם לכן (בגוף ראשון רבים): ״נֵלְכָ֖ה עַד־כֹּ֑ה וְנִֽשְׁתַּחֲוֶ֖ה וְנָשׁ֥וּבָה אֲלֵיכֶֽם״ (כב,ה),

אך כדי באמת להתאחד, הם יצטרכו עוד דור, עוד אדם, עוד ערך שלישי – יעקב, תפארת. אולי גם עבורנו, במקום שאנחנו מבקשים פתרון כזה או אחר, צריך לזכור שקרוב לוודאי שזה גם זה וגם זה, ואנחנו תקוה שעוד מחכה לנו – שעוד נמצא – דרך שלישית מאחדת.

שבת שלום

Parashat Vayera – The Binding of Isaac

It is difficult for us to read the chapter of the Binding of Isaac, especially through our modern, contemporary eyes. I admit: it was not with an easy heart that I drove my son to the gates of the reserve base on October 7th, 2023, hoping that by the time we got there, it would all turn out to be a mistake and we would just go back home… thinking of all the wars I have experienced here, that my family has gone through—and in none of them was I a mother of a soldier…

thinking of our forefather Abraham, and wondering: how is it possible that the man whose entire life symbolizes kindness, who argues with Gd not to destroy a sinful city full of sinners, who bargains and pleads to save one more person here and there, maybe there fifty, maybe forty-five—could so readily obey the divine command that said to him:

“Take now your son, your only one, whom you love, Isaac, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering upon one of the mountains that I will tell you of” (Genesis 22:2)?

And how is it that immediately, “Abraham rose early in the morning, saddled his donkey, took two of his young men with him, and Isaac his son; he split the wood for the burnt offering, and arose and went to the place that God had told him of” (22:3)?

So many verbs (six!) and so much activity in one verse! Abraham rises early in the morning… How could anyone even sleep before such a morning? And not only does he rise—he hastens to fulfill the commandment! By himself, he saddles his donkey, though he has servants and helpers around him. He takes his young men and Isaac; he prepares the wood for the offering—a physically demanding task—and then he gets up and goes.

Abraham, it seems, is 137 years old at this point. Isaac, contrary to the way so many children’s Torah storybooks portray him, is not a small boy being dragged by an old man up the mountain, but a strong young man of about 37, walking with his father of his own free will.

Isaac is often described as a passive figure, his mother’s son. Everything is done for him—even a bride must be brought to him, since on his own he “does nothing.” But let us not be mistaken: his so-called “passivity” is not laziness or inactivity—it is discipline and strength, like a rock standing firm in its place, not out of weakness but out of power and might.

And in this chapter, these two forces—Abraham, the man of kindness, and Isaac, the man of strength—walk “together,” each on his own path. Is one preferable to the other? Or perhaps both are necessary—and how?

In the previous chapter, Sarah said to Abraham: “Cast out this slave woman and her son, for the son of this slave woman shall not inherit with my son, with Isaac” (Genesis 21:10).

Notice the way the children are referred to: she calls Ishmael “her son,” the son of the maidservant—not Abraham’s son, and certainly not their son—who will not inherit “with my son, with Isaac.”

And in the very next verse: “The matter was very grievous in Abraham’s eyes concerning his son” (21:11). His son—and though commentators differ, none dispute that the reference is to Ishmael, Abraham’s son, as opposed to Isaac, Sarah’s son.

And then comes the Binding. And Abraham takes Isaac—his son.

As they walk together, Isaac turns to his father: “My father! And he said: Here I am, my son. And he said: Here is the fire and the wood, but where is the lamb for the burnt offering?

And Abraham said: Gd will see to Himself the lamb for a burnt offering, my son. And the two of them went on together” (Genesis 22:7–8).

For the first time in the Torah, Isaac (now 37 years old!) addresses his father directly—and for the first time, Abraham responds with full attentiveness: “Here I am, my son.”

Isaac asks his question, and Abraham gives his answer that can be understood in two ways (at least):

“Gd will see to Himself the lamb for a burnt offering, (pause) my son”—or—“Gd will see to Himself the lamb (pause) for a burnt offering my son.”

Either way, there is a deep understanding between them: each recognizes that he has a role entirely different from the other’s. Abraham—the man of kindness; Isaac—the man of judgment and might.

We might think that true harmony comes only if they are the same, if they agree on everything. Abraham loved Ishmael—the child he taught about the One Gd and about unbounded kindness—but such limitless, unrestrained kindness, was (and still is) easily turned to harm.

It seems that precisely here, in this most challenging chapter, they both realize that their differences are what will build the path of life to come. Perhaps for the first time, this understanding allows them to truly walk “together”, to fulfill Abraham’s earlier words (in the 1st person plural):

“We will go until there, and we will worship, and we will return to you” (22:5).

Yet to truly unite, they will need one more generation—one more person, one more quality: Jacob, the quality of Tiferet (harmony, beauty).

Perhaps we too, when we seek one solution or another, must remember that the truth is likely both this and that—and that in such situations, we too, are still hoping – waiting —that we will yet find the third, unifying path.

Shabbat Shalom.