OUR PODCAST: https://open.spotify.com/episode/3NwrQXpcW1Otgr30NHBwWf

פרשת תולדות עם יצחק

אני מודה: לקח לי זמן להעריך ולאהוב אפילו, את יצחק.

לכאורה, אדם כל כך ״חסר אישיות״. ״חלש״. ״פסיבי״. אמא שלו מחליטה עם מי ישחק ו- עם מי לא. אבא שלו מעלה אותו לעולה, שם הוא שוכב, כפות על הסלע בלי מילה. עבד אברהם מביא לו אשה שהוא מוצא ליד באר רחוקה. האשה מארגנת איזה ילד הוא יברך. הבן הממשיך מתחפש ומרמה אותו…

אבל יש פסוק אחד שמרמז שעומד מולנו אדם בעל שיעור קומה:

וַיִּגְדַּ֖ל הָאִ֑ישׁ וַיֵּ֤לֶךְ הָלוֹךְ֙ וְגָדֵ֔ל עַ֥ד כִּֽי־גָדַ֖ל מְאֹֽד (בראשית כו,יג).

9 מילים, ובשליש מתוכן – השורש ג.ד.ל, הלוך וגדל, גדל מאד!

מספר הפסוק שלפניו:

וַיִּזְרַ֤ע יִצְחָק֙ בָּאָ֣רֶץ הַהִ֔וא וַיִּמְצָ֛א בַּשָּׁנָ֥ה הַהִ֖וא מֵאָ֣ה שְׁעָרִ֑ים וַֽיְבָרְכֵ֖הוּ ה’.

הפתעה! יצחק לא רק רועה צאן, כמו אביו, בנו ואחרים אלא עובד אדמה, ״יזם״, חקלאי ואפילו מצליח ביותר!

המדרש אומר שהמילים “בארץ ההיא” ו”בשנה ההיא” מספרות שהיתה שנת בצורת והאדמה – קשה, ועדיין, יצחק מוציא פי מאה ממה שהיה צפוי!

אז אולי לא כזה ״חלשלוש״?…

אברהם נחשב לנציג של חסד. יצחק, כמו שרה, נחשב לנציג מידת הדין והגבורה. לאברהם אישיות יוזמת ופועלת בעולם. יצחק מבין את העולם אחרת, וטוב שכך. לו הבין יצחק את העולם כמו שהבין אותו אברהם, אולי היה מנתץ את האלוהים של אביו, כפי שעשה אברהם לתרח, ואנחנו לא היינו כאן היום…

אך יצחק יודע איך להיות ממשיך וזו אחת המשימות הקשות בחיים. הוא מחזיק חזק. העשייה שלו באה מאמונה, וכוח ושלוה פנימיים, והוא הגבר הראשון בתורה, אחרי דורות שרבו ופרו, עליו כתוב שהוא אוהב את האשה – האחת והיחידה – שלו.

אוקי, אתם אומרים, אבל, בכל זאת, מה עם הברכות לעשו ויעקב?

באותו אירוע לא פשוט בפרשה שלנו, אומר יצחק את הפסוק המפורסם: הַקֹּל֙ ק֣וֹל יַעֲקֹ֔ב וְהַיָּדַ֖יִם יְדֵ֥י עֵשָֽׂו (כז,כב). הנה!! האם זו לא הוכחה חותכת? מה, הוא לא יודע מי הבנים שלו?

מרתק לראות את הרגשות הקשים שעולים בנו במפגש עם יצחק. כעס. בושה. ועוד. האם אין לנו כבוד למישהו שיש לו בעיות ראיה, או חולשה? או שמא, הוא מזכיר לנו חלקים בעצמנו שעוד לא עשינו איתם שולם? אניח לזה, ואציע קריאה שונה:

במקום למהר לתקן את יצחק ש”עושה לנו בושות”, נוכל לשמוע אותו מנסה להגיד לנו משהו אחר. יצחק יודע שהדבר הנכון יקרה: שהוא חי בארץ הנכונה ולא עוזב אותה מעולם, שהוא נשוי לאשה הנכונה ולא מוסיף נשים ושפחות גם כשהחיים ביניהם אתגריים, ושהבן הנכון יקבל את הברכה הנכונה.

זה נכון, עיניו כהו מראות. יתכן שאפשר לרמות אותו, במילים חלקות, במנת ציד טרייה ועסיסית, אבל יתכן גם שיכולת הראיה שלו שונה ומתוך כך הוא גם אומר את דברו. הוא יודע, שמי שצריך לקבל את הברכה של אברהם (אחרי הכל, זו לא ברכה פרטית שלו), זה מישהו שעונה לתיאור ״הקול – קול יעקב, והידיים – ידי עשו״, ילד שיש לו תכונות פנימיות, רוחניות כמו של יעקב, וחיצוניות – גוף וחומר – כמו של עשו.

תגידו, אבל אין לו בן כזה??!!

עבור יצחק, זה משני. הוא בעניין של מה שצריך לקרות, מהו הדבר הנכון.

רגע, אבל יש לו רק שני בנים?! זה או-או! אי אפשר גם וגם!

אולי. אולי בעיניים שלנו ״אי אפשר״. אבל יצחק – על פי שמו, לא חי בהווה, אלא בזמן עתיד. ויצחק – למרות עוורונו, רואה דברים שאנחנו עוד לא.

כי יום אחד, יעקב, הילד הטוב שמכין נזיד עדשים ועושה מה שאמא אומרת, יצא לדרכו, גם הוא יצליח כנגד כל הסיכויים, וגם ילחם במלאך, המלאך שהוא שרו של עשו כפי שמלמד אותנו המדרש, ויעקב יוכל לו. יעקב אז יקבל שם חדש – ישראל, השם של הישות שכלפי חוץ היא מחוספסת, לפעמים גסת רוח וחוצפנית, שצריכה ויכולה להתמודד עם עשו וכל צרות העולם הזה. ובפנים, הוא יהיה אותו ״איש תם, יושב אוהלים”, לומד תורה, אוהב חסד ועושה טוב. איך יתכן ששני אלו ידורו בכפיפה אחת בתוך אותו האדם? כן.

זו ההמשכיות הנדרשת מבנו של יצחק. ומאיתנו. ואדם גדול, ההולך וגדל, עד כי גדל מאד, כמו יצחק, הוא זה שדוקא מתוך עוורונו וזקנתו, רואה את זה ומכוון לכך. הוא האיש שהפלישתים, שגרים בארץ בעת ההיא, מקנאים בו, ואין סיכוי שהם מקנאים באיש חלש וחסר יכולת, אלא דווקא בו, שבעשיה השקטה שלו, באהבה שלו, באמונה ובבטחון, הוא מצליח בדרכיו.

יצחק נולד בנס, הנס הראשון בתורה, ומתוכו, הוא מספר לנו עם ישראל, תפקידו, מעמדו, והקיום הניסי שלו לאורך כל ההסטוריה.

חודש כסלו טוב ושבת שלום.

I admit: it took me time to appreciate—and even love—Isaac.

At first glance, he seems like such a “personality-less” man. “Weak.” “Passive.” His mother decides who he plays with and who he won’t. His father takes him up the mountain as an offering, and there he lies, bound on the rock, not uttering a word. Abraham’s servant brings him a wife found by a distant well. His wife engineers which child he blesses. The son dresses up and deceives him…

But there is one verse that hints that we are in fact facing a man of stature:

“The man grew, and continued to grow, until he became exceedingly great.” (Genesis 26:13)

Nine words in the Hebrew, and in three of them—the root G-D-L, “grow”, continuing to grow, growing exceedingly!

The previous verse says:

“Isaac sowed in that Land and in that year found a hundredfold, and Hashem blessed him.”

Surprise! Isaac is not only a shepherd like his father, his son, and many others; he is a farmer, an “entrepreneur,” a cultivator of the Land—and a remarkably successful one!

The midrash teaches that the terms “in that land” and “in that year” tell us it was a year of drought and the Land was harsh, and still Isaac produced one hundred folds what was expected!

So maybe he’s not such a “weakling” after all…

Abraham is viewed as the representative of chesed (lovingkindness). Isaac, like Sarah, is seen as the representative of din and gevurah—judgment and strength. Abraham has an initiating, active personality. Isaac understands the world differently—which that is a good thing for us. Had Isaac understood the world the way Abraham did, perhaps he would have shattered his father’s Gds, just as Abraham shattered Terach’s idols, and we would not be here today…

But Isaac knows how to be a continuator, and that is one of the hardest tasks in life. He holds firm. His actions come from faith, inner power, and tranquility, and he is the first man in the Torah—after generations of “being fruitful and multipling”—of whom it is written that he loves his wife, his one and only.

Okay, you say, but what about the blessings to Esau and Jacob?

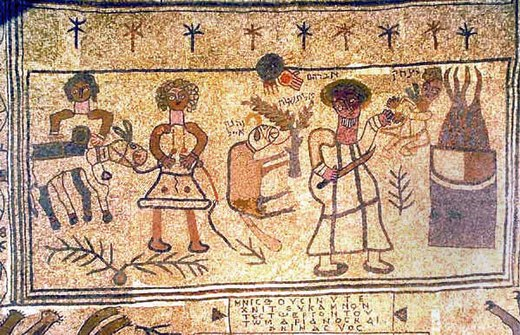

In that complicated scene in our Torah portion, Isaac says the famous verse: “The voice is the voice of Jacob, but the hands are the hands of Esau.” (27:22)

There! Isn’t that proof? What—he doesn’t know his own sons one from the other?

It’s fascinating to see the difficult emotions that arise in us when we encounter Isaac—anger, embarrassment, and more. Do we have no respect for someone with impaired vision or weakness? Or perhaps he reminds us of parts of ourselves with which we have not yet made peace?

I’ll set that aside; Let’s look at a different reading:

Instead of rushing to “fix” Isaac, who “embarrasses us”, we might listen as he tries to tell us something else. Isaac knows that the right thing will happen: that he lives in the right Land and never leaves it, that he is married to the right woman and does not add wives or concubines even when their marital life is challenging, and that the right son will receive the right blessing.

True, his eyes are dim. Perhaps he can be deceived—with smooth words and a fresh, juicy dish of steak. But perhaps his sight is simply different, and from that place, he speaks.

He knows that the one who should receive Abraham’s blessing (after all, it is not his own private blessing) must be someone who fits the description: “the voice is the voice of Jacob, and the hands are the hands of Esau”—a child with Jacob’s spiritual, inner qualities and Esau’s physical, outward ones.

You’ll say, “But he doesn’t have such a son!”

For Isaac, that’s secondary; he’s about what should happen, what’s the right thing.

Wait, but he only has two sons! It’s either-or! You can’t have both!

Perhaps. Perhaps in our eyes it is “impossible.” But Isaac, true to his name, does not live in the present but in the future. Isaac, despite his blindness, sees things we do not yet see.

For one day Jacob, the good child who cooks a lentil stew and does what his mother says, will go out into the world; he too will succeed against all odds; he will wrestle with an angel, the angel who is Esau’s guardian according to the midrash, and Jacob will prevail. Then Jacob will receive a new name – Israel – the name of a being that is externally rough, sometimes brazen or defiant, who must and can contend with Esau and the hardships of this world.

And inside, he will remain that “simple man, dwelling in tents,” a learner of Torah, a lover of kindness, a doer of good.

How can both reside within the same person?

Yes.

This is the continuity required of Isaac’s son. And of us.

And a great man, one who “grew and continued to grow until he was exceedingly great,” like Isaac, is the one who, precisely from within his blindness and old age, sees this and directs the future toward it.

He is the man whom the Philistines, people who live in the Land at that time, envy—and there is no chance they envy a weak or incapable man, but rather one who, through his quiet work, his love, his faith and confidence, succeeds in his ways.

Isaac was born through a miracle – the first miracle in the Torah – and from that miracle he teaches the People of Israel their role, their stature, and their miraculous existence throughout history.

Chodesh Kislev tov & Shabbat Shalom.