| How are you, she asks me when we meet for our morning coffee. Thank Gd, I answer with a big smile, everything is good. She looks at me, wondering, checking, Everything? Good? I think for a moment, looking around, at the people, hurrying on their way like bees among flowers, from store to store to store, the flowing traffic, the trees, the sun shining, the blue sky, the view beyond… I show with my hand in a wide movement, everything is good. Wait, she stops me, don’t you hear the news? Don’t you follow what’s happening? Have you heard about…? And also about…? So how is everything good? Look! I answer, pointing around again with my hand. This? She says in a voice that is a mixture of surprise and mockery, this?? This is “everything is good”? This – is not enough!!! | מה שלומך, היא שואלת אותי כשאנחנו נפגשות לקפה של בקר. ב”ה, אני עונה בחיוך גדול, הכל טוב. היא בוחנת אותי בפליאה, בודקת. הכל? טוב? אני חושבת רגע, מסתכלת החוצה, אל האנשים, ממהרים לדרכם כמו דבורים בין פרחים, מחנות לחנות לחנות, התנועה הזורמת, העצים, השמש הזורחת, השמים הכחולים, הנוף שמעבר… אני מראה בידי בתנועה רחבה, הכל טוב. רגע, היא עוצרת אותי, את לא שומעת חדשות? לא עוקבת אחרי מה שקורה? שמעת על…. ? וגם על….?? אז איך הכל טוב? תסתכלי! אני עונה, מראה בידי שוב. זה? היא אומרת לי בקול שחלקו הפתעה וחלקו לגלוג, זה?? זה – “הכל טוב”? זה – לא מספיק!!! |

| These days mark 50 years since the Yom Kippur War, and people (like me 😊) who have been telling the world for years that they are 29 years old, maximum 39, and a bit, reminisce about that Shabbat, that week, those events. Archives are opened, films are edited and screened, and things we didn’t know suddenly come up: oh, right, I didn’t remember that…. I didn’t even know that then… who believed that… | בימים אלו מציינים 50 שנה למלחמת יום הכיפורים, ואנשים (כמוני 😊) שכבר שנים מספרים לעולם שהם בני 29, מקסימום 39 וקצת, מעלים זכרונות מאותה שבת, מאותו שבוע, מאותם אירועים. ארכיונים נפתחים, סרטים נערכים ומוקרנים, ודברים שלא ידענו, פתאום עולים: אה, נכון, לא זכרתי ש…. אז בכלל לא ידעתי ש… מי האמין ש… |

| And I think about the past, which, contrary to its name, didn’t pass at all but rather is constantly changing, and I wonder if it’s possible for us to learn a little humility in our present days, not only for “them” but also for “us”, and how this time will look 50 years from now… And I also replay over and over my own memories of that Yom Kippur, the alarm, the afternoon at the synagogue – people with small transistors under their tallitot, waiting to hear their unit’s code, the ambulances screeching in the quiet streets, rattling the silent holiday, and the week after, the news, the messages, the names, the phone ringing… | ואני חושבת על העבר, שבניגוד למה שנדמה שהוא חלף ועבר, הוא כל הזמן הולך ומשתנה, ואני תוהה, אם אפשר שנלמד בהווה שלנו קצת ענווה, לא רק “להם” אלא גם “לנו”, ואיך כל זה יראה בעוד 50 שנה… ואני מגלגלת שוב ושוב גם את הזכרונות הפרטיים שלי של אותו יום כיפור, את האזעקה, את שעות אחהצ בבית הכנסת – אנשים עם טרנזיסטורים קטנים מתחת לטליתות, מחכים לשמוע את הקוד ליחידה שלהם, את האמבולנסים צורמים ברחובות השקטים, מחרידים את שלוות החג, ואת השבוע אחרי, החדשות, הידיעות, השמות, צלצול הטלפון… |

| And one intersection that by now already has traffic lights and new buildings have risen there and gardeners have replaced flowers and trees, and countless people have passed through it, day after day, and still, every time I pass through it, I’m still standing there with a few friends, a group of pre-teens to whom the future has been hastened all at once , and we are holding buckets with dark blue paint and rough brushes, stopping cars to quickly paint their headlights before everything is blacked-out, and it’s almost dark and we have to hurry before maybe another siren, and one man, in a knitted kippa, rushing, maybe to build his sukkah, calling, thank you very much, may you merit many mitzvot , Shana Tova and a happy holiday! And I don’t understand… | וצומת אחת שבנתיים כבר יש בה רמזורים ובנו בה בניינים חדשים וגננים החליפו פרחים ועצים, ואינספור אנשים עברו בה, יום יום יום, ועדיין, כל פעם שאני עוברת בה, אני עומדת שם עם כמה חברים, חבורת ילדים בני עשרה שהקדימו לנו את העתיד בבת אחת, ואנחנו מחזיקים דליים עם צבע כחול כהה ומברשות גסות, עוצרים מכוניות למהר ולצבוע את פנסיהן לפני ההאפלה, וכבר כמעט חושך וצריך למהר לפני שאולי עוד אזעקה, ואיש אחד, בכיפה סרוגה, ממהר, אולי לבנות סוכה, אומר לנו, תודה רבה, תזכו למצוות, שנה טובה וחג שמח! ואני לא מבינה…. |

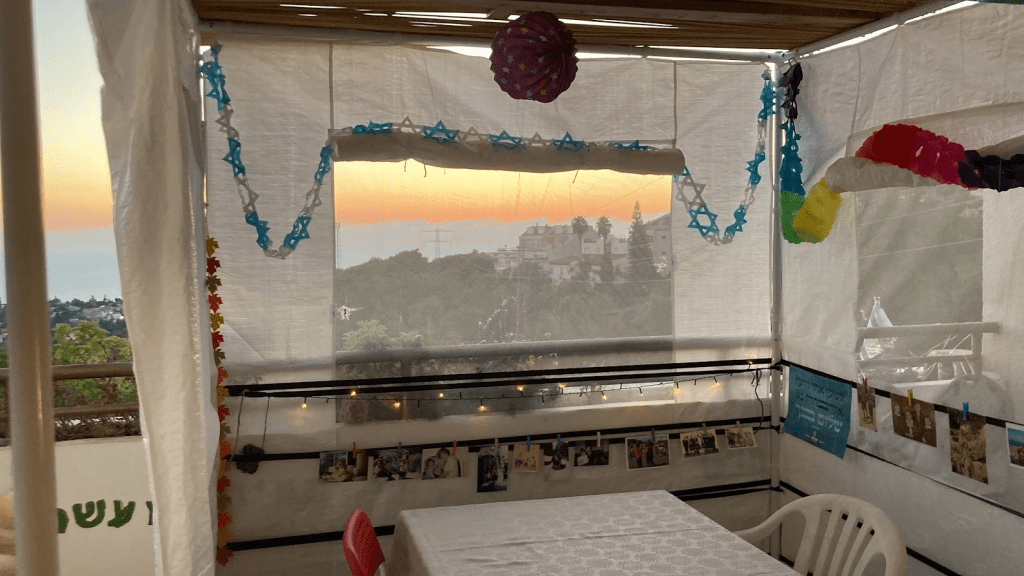

| It has become easier and easier to celebrate Sukkot, to build a Sukkah, to get s’chach, and the four species; and the new train to Jerusalem, makes the trip easier, even if it’s crowded, reminding us of the pilgrimage. And only one thing remains incomprehensible: the commandment to be happy. How did the Torah write, “And you will rejoice”, (Leviticus 23:40), and later “And you will rejoice at your feast”, and again – “And you were only joyful” (Deuteronomy 16:14-15)? How can we be commanded to be joyful? Is joy not an “emotion” that “depends”? We have another strange commandment in the Torah: “You shall love” the Lord your God (Deuteronomy 6:5), your fellow (Leviticus 19:19) and the stranger (Leviticus 19:4). How can we be commanded to love? | נהיה קל יותר ויותר לחגוג את סוכות, לבנות סוכה, להשיג סכך, וגם ארבעת המינים, והרכבת החדשה לירושלים, תקל על הנסיעה, גם אם תהיה עמוסה, ותדמה לנו עליה לרגל. ורק דבר נשאר בלתי מובן: מצוות השמחה. איך כתבה התורה, “ושמחתם”, (ויקרא כג:40), ואח”כ “ושמחת בחגך”, ושוב – “והיית אך שמח” (דברים טז:14-15)? איך אפשר לצוות עלינו להיות שמחים? האם השמחה היא לא “רגש” ש”תלוי”? יש לנו ציווי מוזר נוסף בתורה: “ואהבת”, כתוב, גם את ה’ אלוהיך (דברים ו,ה), גם את רעך (ויקרא יט, יט) גם את הגר (ויקרא יט, לד). איך אפשר לצוות אותנו לאהוב? |

| There is a possibility that we perceive things differently. Maybe the Torah didn’t speak of an emotion, as we think nowadays, but an action. Love of one’s neighbor is a consequence of the understanding that we are all created in Gd’s image, and it should be expressed in certain practical things – charity, visiting the sick, comforting the bereaved, hospitality – regardless of our feeling, or, in the hope that the action will affect the feeling, instead of waiting for the opposite to happen. | יש אפשרות שאנחנו תופסים את הדברים אחרת. אולי לא מדובר ברגש, כמו שנדמה לנו בימינו, אלא בעשייה. אהבת רעך היא תולדה של ההבנה שכולנו נבראנו בצלם אלוהים, והיא צריכה להתבטא בדברים מעשיים מסוימים – צדקה, ביקור חולים, ניחום אבלים, הכנסת אורחים – בלי קשר להרגשה, או, בתקווה שהעשיה תשפיע על ההרגשה, במקום לחכות שיקרה ההיפך. |

| And there is another possibility, which is – that we are commanded on our feeling, and that the Torah wants to teach us that joy is not a result, but a source. It’s not something that happens to us when all the conditions are right and perfect, and we have everything we want quite precisely, but something that we choose, as a song says, ‘to get up tomorrow morning with a new song in our heart’. True, it is not easy, and might not feel “natural”, but the Torah does not command us – neither the easy nor the “natural”, and not the impossible. Accordingly, happiness is not a place to reach, one day, when we chance upon the golden bucket over the rainbow, but it’s the ticket to go. Not for nothing is Sukkot called “The Holiday of Ingathering”, the holiday in which we must go out into the field and gather the fruit of our labor. What if I’m not a farmer? even then Yes, even then. We must go out and collect all the good things we have done and happened to us this year, look, enjoy and delight, celebrate and be happy. And when the voice comes up to tell us, “it’s not enough”, it’s our job to tell it, “It’s a lot”! | וישנה אפשרות נוספת, וזה – שכן יש אפשרות לצוות על הרגש, ושהתורה רוצה ללמד אותנו שהשמחה היא לא תוצאה, אלא מקור. היא לא משהו שקורה לנו כשכל התנאים נכונים ומושלמים, ויש לנו את כל מה שאנחנו רוצים בדי-בדיוק, אלא משהו שאנחנו בוחרים בו, “לקום מחר בבקר עם שיר חדש בלב”. נכון, זה לא קל, וזה לא מרגיש לי “טבעי”, אבל התורה לא מצווה אותנו – לא על הקל ולא על ה”טבעי”, וגם, לא על הבלתי אפשרי. לפי זה, השמחה היא לא מקום להגיע אליו, יום אחד, כשנפגוש בדלי הזהב מעבר לקשת בענן, אלא היא כרטיס היציאה לדרך. לא לחינם נקרא סוכות חג האסיף, החג בו עלינו לצאת לשדה ולאסוף את פרי עמלנו. ומה אם אני לא חקלאי? גם אז. כן, גם אז. עלינו לצאת ולאסוף את כל הטוב שעשינו ושקרה לנו השנה, להסתכל, להנות ולהתענג, לחגוג ולשמוח. וכשיעלה הקול שיגיד לנו, אבל “זה לא מספיק”, תפקידנו להגיד לו, “זה המון”! |

| In the famous meeting between Jacob and Esau, after they had not seen each other for 20 years, Jacob presents Esau with a handsome offering, and Esau tells him, “I have a lot”, meaning, ‘actually, no need, I have a lot of property and I don’t need gifts from you. Jacob insists and says, “please take my blessing… I have all” (Genesis 33:9-11). How can we understand the difference between “I have a lot” and “I have all”? Or more correctly, as the Sfat Emet asks: “How can a person say “all”, when there were so many things that we don’t have”? | בפגישה המפורסמת בין יעקב ועשו, אחרי שלא התראו 20 שנה, יעקב מגיש לעשו מנחה נאה, ועשו אומר לו, “יֶשׁ־לִ֣י רָ֑ב”, כלומר, בעצם, לא צריך, יש לי הרבה רכוש ואני לא צריך מתנות ממך. יעקב מתעקש ואומר, “קַח־נָ֤א אֶת־בִּרְכָתִי֙… יֶשׁ־לִי־כֹ֑ל” (בראשית לג, ט-יא). איך ניתן להבין את ההבדל בין “יש לי רב” ל”יש לי כל”? או יותר נכון, כפי ששואל השפת אמת: “איך יוכל אדם לומר כל והרי כמה דברים היו שלא היה לו”? |

| It seems that the “a lot” is a quantitative and relative plurality, and still shows a feeling of lack, while the “all” implies the connection to the Source of Abundance, and a feeling of “all”, whether there is or not “all”. Esau at this point is very satisfied with his power, but also depends on what and how much he has. Jacob clarifies that he is not concerned with quantity, and therefore does not depend on it. It is said of Jacob that he is given an “inheritance without limits” (tractate Shabbat 118:a): because of this ability to feel that he has “all”, he is connected to the Infinite, beyond the “straits”, beyond the limitations and narrow boundaries of what is and what is not. The Sfat Emet adds and says that “…he who clings to the Upper Root, what he has is like “all”, for “all” is something that has a vital point from Gd, and in this point all is included”… | נראה שה”רב” הוא ריבוי כמותי ויחסי, ועדיין מראה על תחושת חוסר, בעוד ה”כל” מרמז על הקשר למקור השפע, ותחושה של “כל”, בין אם יש ובין אם אין “הכל”. עשו בשלב זה, מאד מרוצה מכוחו, אך גם תלוי במה וכמה שיש לו. יעקב מבהיר שהוא לא עסוק בכמות, ולכן לא תלוי בכך. על יעקב נאמר שנותנים לו “נחלה בלי מיצרים” (שבת קיח:א): בגלל היכולת הזו להרגיש שיש לו “כל”, הוא קשור לאינסוף, מעבר ל”מיצרים”, מעבר למגבלות ולגבולות הצרים של מה שיש ומה שאין. השפת אמת מוסיף ואומר, ש”…מי שדבוק בשורש עליון מה שיש לו הוא בחינת כל, כי כל דבר יש בו נקודת חיות מהשי”ת ובנקודה זו כלול הכול”… |

| Each of our forefathers has a different holiday from the three pilgrimage festivals: Abraham is associated with Pesach; Isaac – with Shavuot, while Jacob’s holiday – is the holiday of Sukkot, the holiday of joy, the holiday of the feeling of “I have all”. May we win merit as well. | לכל אחד מהאבות, יש חג אחר משלושת הרגלים: אברהם קשור לפסח, יצחק – לשבועות, ואילו החג של יעקב – הוא חג סוכות, חג השמחה, חג תחושת ה”יש לי כל”. מי יתן ונזכה. |

שבת שלום וחג שמח! SHABBAT SHALOM & HAPPY SUKKOT