PODCAST: https://open.spotify.com/episode/4NGHRrNK3KHrmFo3oO4GRP

וירושלים מן התורה מנין? או “תִדְרְשׁ֖וּ וּבָ֥אתָ שָֽׁמָּה”

כמה פעמים מוזכרת ירושלים, כך בשמה זה, בתורה? אחרי הכל, עיר הקודש בתוך ארץ הקודש אליה מועדות פנינו במשך כל ארבעים שנות המסע במדבר! ועוד לפני כן, אברהם. יצחק. יעקב…

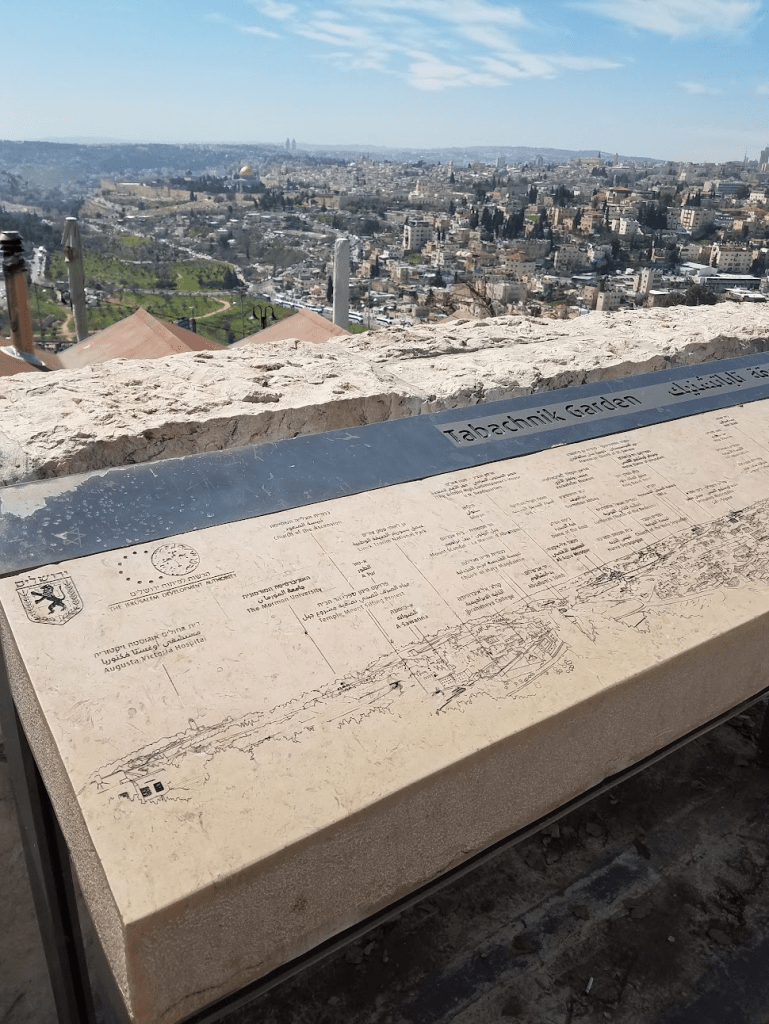

אבל ירושלים לא מוזכרת בשמה בתורה כך אפילו פעם אחת! רק לאחר-מכן, בספר יהושע שמספר לנו על הכניסה לארץ ועל חלוקת הארץ לשבטים, מוזכרת ירושלים ואפילו בדייקנות מדהימה שאפשר לזהות כיום. אבל בתורה – רק רמזים.

כשאברהם – אז עדיין אברם, חוזר מהנצחון על ארבעת המלכים, מלכיצדק “מלך שלם” יוצא לקראתו (בראשית, יד,יח). מאוחר יותר (בפרק כב), אברהם מצווה להעלות את יצחק לעולה על “הר המוריה”, וכשמסופר על שלמה שהחל לבנות את בית ה’ “בִּיר֣וּשָׁלִַ֔ם בְּהַר֙ הַמּ֣וֹרִיָּ֔ה”, אנחנו מבינים שזה אותו המקום (דברי הימים ב, ג:א).

המדרש (בראשית רבה נו,י) מסביר את שמה של ירושלים כשילוב בין שני פסוקים: במקום אחד נאמר שאברהם קרא ״שֵׁם הַמָּקוֹם הַהוּא ה’ יִרְאֶה” (בראשית כב,יד) ובפסוק אחר נאמר ששם, בנו של נח, קרא לאותו המקום שלם, שנאמר ״וּמַלְכִּי צֶדֶק מֶלֶךְ שָׁלֵם” (בראשית יד, יח).

הקב”ה התלבט איך לקרוא למקום הזה, וחשב לעצמו:

אִם קוֹרֵא אֲנִי אוֹתוֹ יִרְאֶה כְּשֵׁם שֶׁקָּרָא אוֹתוֹ אַבְרָהָם, שֵׁם, אָדָם צַדִּיק, מִתְרָעֵם, וְאִם קוֹרֵא אֲנִי אוֹתוֹ שָׁלֵם, אַבְרָהָם אָדָם צַדִּיק מִתְרָעֵם, אֶלָּא הֲרֵינִי קוֹרֵא אוֹתוֹ יְרוּשָׁלַיִם כְּמוֹ שֶׁקָּרְאוּ שְׁנֵיהֶם, יִרְאֶה שָׁלֵם, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם.

כלומר, שמה של ירושלים הוא שילוב של יראה ושלם. אז למה לא נקראה יראהשלם?

כדי לא להפלות את אברהם לטובה, שיקבל 4 אותיות בשם העיר הקדושה לעומת שם שיקבל רק 3, במילה יראה – ״הולחמו״ שתי האותיות האחרונות לאות אחת: א+ה=ו. כך נהייה שם המקום מ״יראהשלם״ ל-ירו-שלם. הקב”ה הוסיף עוד אות אחת בשם העיר, האות יוד, האות המסמלת את שמו. עכישו שמה מושלם – הוא מסמל יראה ושלום יחד עם שם ה’. בסה״כ – 7 אותיות כמספר הקנים במנורה וכמספר המסמל שלמות בטבע.

בפרשת השבוע שלנו נאמר:

כִּ֠י אִֽם־אֶל־הַמָּק֞וֹם אֲשֶׁר־יִבְחַ֨ר ה’ אֱלֹֽהֵיכֶם֙ מִכָּל־שִׁבְטֵיכֶ֔ם לָשׂ֥וּם אֶת־שְׁמ֖וֹ שָׁ֑ם לְשִׁכְנ֥וֹ תִדְרְשׁ֖וּ וּבָ֥אתָ שָֽׁמָּה (דברים יב:ב).

למה לא נכתב במפורש לבנות את בית המקדש בירושלים?

מאות שנות פרשנות הורישו לנו הסברים רבים ושונים, כל אחד נפלא לפי דרכו.

אביא כאן רק כמה, כל אחד יחודי בדרכו ומשלים את חברו:

החזקוני הסביר שהמקום לא מזוכר בדיוק כי השכינה שרתה בכמה מקומות ו״חייב אדם לשנות לתלמידו בדרך קצרה״. כמובן שהפסוק ארוך יותר מרשימת המקומות אך כנראה כוונתו שיותר קצר ונכון ללמד כלל ועיקרון מאשר פרטים.

האברבנאל כתב שהעיקר הוא, במיוחד על רקע הפסוקים הקודמים בפרשה שלנו, שהמקום איננו בכל המקומות שהעמים האחרים היו עובדים לאלוהיהם אלא מקום אחד שמשקף את האל האחד.

הרמב”ם אומר שבכוונה לא נאמר שם המקום משלוש סיבות: 1. מפני שאם העמים האחרים ידעו איפה המקום, הם ילחמו עליו. 2. מי שהמקום בידו, עלול לעשות הכל להרוס אותו כליל. ו-3. כל שבט עלול לבקש שבית המקדש יהיה בנחלתו, מה שיגרום לריבים ומחלוקות. לכן קודם כל יהיה מלך, ואחדות בעם, ורק אחר-כך, יבנה בית המקדש. אלו הן סיבות שהוכחו כנכונות לאורך ההיסטוריה.

לעומתם, פירוש על ספר דברים מבקש שנשים לב שנאמרה בפסוק המלה ” תִדְרְשׁ֖וּ” – אנחנו צריכים לעבוד ולעבור תהליך כדי לגלות את המקום. אחרי שנטרח, נחפש ונמצא, יהיה נביא שיאשר לנו שאכן, כאן הוא, אך אל לנו לשבת בחוסר מעש ולחכות לאותו הנביא. על דרך המשל, אנחנו במעין חפש את המטמון עם הקב”ה: המטמון כבר שם. קדושתה של ירושלים הינה מאז ועד עולם, ובלתי תלויה בנו. אבל עלינו לגלות את המקום ולהאיר את יופיו.

יכול היה להיות קצר, מדויק וברור לתורה להגיד, לכו לירושלים! אבל התורה בחרה להוסיף לנו ״תדרשו״… במיוחד בתקופה זו, בה לכולנו יש את ״ה״תשובה ״ה״נכונה ל״הכל״ במיידי, פרשת ״ראה״ כולה בענין בחירה, והספרי מזכיר שאולי לא פחות מהפתרון, גם ה״לדרוש״ חשוב.

לקראת חודש אלול טוב ושבת שלום

How many times is Jerusalem mentioned by its name in the Torah?

After all, it’s the Holy City in the Holy Land toward which our journey in the desert was directed for all forty years! And even before that—Abraham, Isaac, Jacob…

But the name Jerusalem is not mentioned even once in the Torah! Only later, in the book of Joshua, which tells of the entry into the Land and its division among the tribes, is Jerusalem mentioned—and even with incredible precision that can still be recognized today. But in the Torah itself – only hints…

When Abraham—then still Abram—returns from the victory over the four kings, Malkizedek, King of Shalem, comes out to greet him (Genesis 14:18). Later on (chapter 22), Abraham is commanded to offer Isaac as a burnt offering on “Mount Moriah,” and when we read that Solomon began building the House of God “in Jerusalem, on Mount Moriah” (2 Chronicles 3:1), we understand – it’s the same place.

The Midrash (Genesis Rabbah 56:10) explains Jerusalem’s name as a combination of two verses: in one place, it says that Abraham called the place “Hashem Yir’eh” (“Gd will see”) (Genesis 22:14), and in another, that Shem, the son of Noah, called it Shalem, as it says: “And Melchizedek, King of Shalem” (Genesis 14:18).

Gd “struggled” with what to name the place, thinking:

“If I call it Yir’eh as Abraham named it, Shem, a righteous man, will be upset. And if I call it Shalem as Shem named it, Abraham, also a righteous man, will be upset. Therefore, I will call it Jerusalem (Yerushalem), as both of them named it – Yir’eh + Shalem = Yerushalem.”

So the name Jerusalem is a combination of Awe (Yir’eh) and Wholeness/Peace (Shalem).

So why not call it Yirehshalem?

In order not to favor Abraham with four letters (in Yir’eh) while Shem would only get three (in Shalem), the two final letters of Yir’eh—aleph and heh—were “merged” into one letter: vav. This is how the name evolved from Yirehshalem to Yeru-shalem.

Gd then added one more letter—yod, symbolizing His Name.

Now the name is complete – it represents awe and peace along with Gd’s Name.

Altogether, it contains seven letters, like the seven branches of the menorah and the number representing completeness in nature.

In our weekly Torah portion, we read:

“But only to the place that the Lord your God will choose from all your tribes to place His name there—you shall seek His dwelling and come there.”

(Deuteronomy 12:5)

So why isn’t it stated explicitly that the Temple should be built in Jerusalem?

Hundreds of years of commentary have given us many different and beautiful explanations.

I will bring here just a few, each unique in its approach and complementary to the others:

- The Chizkuni explains that the place isn’t mentioned precisely because the Divine Presence rested in several places over time, and “a person must teach his student in a concise manner.” Of course, the verse is longer than just listing locations, but perhaps his intention was that it’s better to teach a general principle than to get lost in specific details.

- The Abarbanel writes that the main point—especially in light of the preceding verses in our portion—is that the chosen place will not be like all the other locations where the nations worshiped their gods, but a single place that reflects the One true God.

- Maimonides (Rambam) says that the location was deliberately not revealed for three reasons:

- If the other nations knew the place, they would fight to take it.

- Whoever held it might seek to destroy it completely.

- Each tribe might claim the Temple should be in its territory, causing arguments and division.

Therefore, first there had to be a king and unity among the people—and only then, the Temple could be built.

These concerns have unfortunately proven true throughout history.

In contrast, one commentary on Deuteronomy points out that the verse uses the word “you shall seek (tidreshu)“—meaning that we must work and undergo a process to discover the place.

After we exert effort and truly search, a prophet will confirm to us that yes, this is the place.

But we must not sit idly by and wait for that prophet to come.

As a metaphor, it’s like a divine treasure hunt: the treasure is already there.

The sanctity of Jerusalem exists from eternity and is independent of us.

But it is up to us to uncover the place and reveal its beauty.

The Torah could have simply stated: Go to Jerusalem!

But instead, it added the word “you shall seek (tidreshu)“…

Especially nowadays, when everyone thinks they have the immediate and correct answer for everything, this Torah portion of Re’e speaks to us about choice, and the Sifrei (Midrashic commentary) reminds us that perhaps no less than the solution itself, the seeking is what really matters.

With blessings to a good new month of Elul & Shabbat Shalom!

Zoom class in Oakland on the topic:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NMvoafaQZ8Q