מצה זו שאנו אוכלים, על שום מה? (English below)

מצה – מלשון – למצות, שהכל מצוי בה.

בספר דברים (בתחילת פרק ט״ז, פסוקים א- ג) נאמר:

שָׁמוֹר֙ אֶת־חֹ֣דֶשׁ הָאָבִ֔יב וְעָשִׂ֣יתָ פֶּ֔סַח לַה׳ אֱלֹהֶ֑יךָ… כִּ֞י בְּחֹ֣דֶשׁ הָֽאָבִ֗יב הוֹצִ֨יאֲךָ֜ ה׳ אֱלֹהֶ֛יךָ מִמִּצְרַ֖יִם לָֽיְלָה׃

וְזָבַ֥חְתָּ פֶּ֛סַח לַה׳ אֱלֹהֶ֖יךָ צֹ֣אן וּבָקָ֑ר בַּמָּקוֹם֙ אֲשֶׁר־יִבְחַ֣ר ה׳ לְשַׁכֵּ֥ן שְׁמ֖וֹ שָֽׁם׃ לֹא־תֹאכַ֤ל עָלָיו֙ חָמֵ֔ץ שִׁבְעַ֥ת יָמִ֛ים תֹּֽאכַל־עָלָ֥יו מַצּ֖וֹת לֶ֣חֶם עֹ֑נִי כִּ֣י בְחִפָּז֗וֹן יָצָ֙אתָ֙ מֵאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרַ֔יִם לְמַ֣עַן תִּזְכֹּר֔ אֶת־י֤וֹם צֵֽאתְךָ֙ מֵאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרַ֔יִם כֹּ֖ל יְמֵ֥י חַיֶּֽיךָ׃

מה פירוש הביטוי הזה – ״לחם עוני״?

בגמרא במסכת פסחים אנחנו מוצאים דיון על כך – האם מדובר בלחם של ימי העבדות עצמם? לחם שמרמז על צער וצרות – ולכן, מצרים? אולי על לחם של העני עצמו?

או שמא, כפי שאומר רבי עקיבא בשם שמואל:

“לחם עוני” כלומר – לחם שעונין (אומרים) עליו דברים הרבה – הלחם עצמו מספר את סיפור ההגדה של פסח?

המצה היא לחם שאין בו שמן, ביצים או מיני משקים, אלא רק מים וקמח. המצה עניה מ-טעמים, אבל דוקא העוני הזה עושה אותה חופשיה מהשעבוד לחומר. לכן – היא בעצמה בת חורין, וכך היא מספרת את סיפור העבדות והגאולה.

יוצא שבין שלושת המאכלים העיקריים בליל הסדר – פסח, מצה ומרור:

מרור – זכר לעבדות, ולמרירות במצרים, מלשון צר, צרות וצרות – בחולם ושורוק

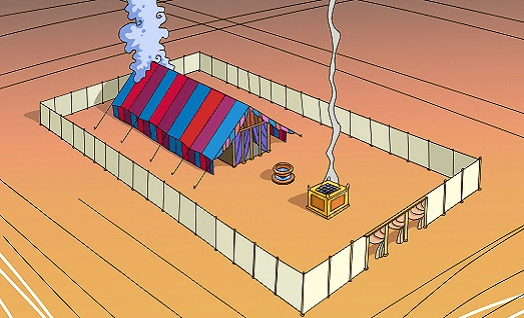

קרבן הפסח – זכר לחירות, ליציאה ממצרים, ליכולת לעבוד את ה׳ בדרכנו, נוכחות בארץ הקודש, בבית המקדש

ואילו המצה – היא זכר גם לעבדות וגם לגאולה.

ואולם – לא די בכך. המצה נמשלה גם כזכר לתורת ישראל, עם ישראל וארץ ישראל.

במכילתא (1א) דרשו חז”ל את הפסוק “ושמרתם את המצות” (שמות יב, יז) – “אל תקרא ״ושמרתם את המצות״, אלא ושמרתם את המצוות, כדרך שאין מחמיצין את המצה כך אין מחמיצין את המצוה, אלא – אם באה לידך, עשה אותה מיד”. ומבואר שיש חובת זריזות בקיום מצווה, מייד כשבאה לידינו.

זו תורת ישראל.

ועם ישראל? הרב קוק כותב מאמר מופלא על המצה וממשיל את עם ישראל לגרגרי קמח וסולת שביחד עם המים, הפכו לבצק.

הגרגרים – זו הזהות הלאומית שלנו, כעם. יחד עם מים, רמז לכוח העליון של הקב״ה, מפני שבעם ישראל – התחלנו להיות עם יחד עם קבלת גילוי השכינה. בעצם, אין בזיכרון הלאומי שלנו זכר לזמן שבו האומה חיתה ללא אלוהים.

ואז, ממשיך הרב קוק: “זה החומר אשר יובא באש, והיה ללחם, היסוד המזין, הממשיך את חיי האדם בצורתם המפותחת”

כלומר – בזמן הגאולה ממצרים, הופיע עלינו הקב״ה, ו״אפה״ אותנו בצורה כזו שלא ניתן לבצק הזה – לנו – להחמיץ, כלומר – להפריד אותנו ממנו ו/או מהתורה, ובכך, נוצרה לנו האפשרות להשפיע תוכן מיוחד, כפי שהוא אומר ״ליתן חיי עולם לכל האנושיות כולה במשך הדורות מהחל עד כלה באחרית הימים״.

והמצה היא גם תזכורת למעלת ארץ ישראל. גם החיבור של עם ישראל לארץ ישראל הוא ייחודי. עמים אחרים נקשרים לארצם, בד״כ בגלל מה שהארץ מטבעה נותנת להם – מפני שיש לה אקלים מסוים, אוצרות טבע, אפשרות לפתח חקלאות, תעשיה, הרגלים, נוחות, הסטוריה, תרבות.

החיבור שלנו לארץ ישראל הוא חיבור של פשטות ועניות. ארץ שמתוארת ע״פ מה שאין בה: “לֹ֣א כְאֶ֤רֶץ מִצְרַ֙יִם֙ הִ֔וא” שאין בה מים – “למטר השמים תשתה מים” (דברים יא, יא). ארץ שרבים יגידו עליה שהיא ״עניה״, כמו המצה, אבל – היא ארץ של הקב״ה, ועל כן לא נחסר כל בה.

וכל זה ועוד – טמון במצה.

בעזרת המצה אנחנו קוראים לכולם לבוא לאכול איתנו: הא לחמא עניא! כל דיכפין יתא ויאכל! אכילת המצה היא לימוד חווייתי שמשחזר את סיפורנו, לא רק כסיפור היסטורי רחוק, אלא כענין קיומי עכשווי ועתידי. לא רק כיחידים אלא כעם שלם, שלא מאבד תקוה, ש״בכל דוד ודור״ קם ויוצא ממצרים, ממקום חסר תקוה, לבשורה של גאולה.

המצה אם נלעס אותה במהירות, היא תרגיש תפלה, חסרת טעם ומשמעות, ״דיקט״, קרטון, וכו, אך אם נלעס אותה לאט, המתיקות שבה תשתחרר ונרגיש אותה במלוא פינו – מתיקות של חירות ואחדות ופריחה בארצנו. לכן גם נאמר לנו לא להפטיר אחר הפסח אפיקומן, שיהיה זה הטעם שנשאר איתנו מהלילה זה והלאה, מעורר בנו השראה לצאת – יחד – עם אחד כאיש אחד, למסע הזה, לצאת ממקום הצרות והצרות, לחצות את הים, לקבל תורה ולהגיע אל הארץ המובטחת.

שבת שלום וחג פסח שמח!

This matzah that we eat, what is it all about?

Matzah – possibly comes from the Hebrew word lematzot, to fulfill, to get the most out of something (to “juice it out”) for everything can be found in the matzah….

In the book of Deuteronomy (at the beginning of chapter 16, verses 1-3) it is said:

Observe the month of Aviv (spring) and offer a passover sacrifice to Hashem your Gd for it was in the month of Aviv, at night, that Hashem your Gd freed you from Egypt. You shall slaughter the passover sacrifice for Hashem your Gd, from the flock and the herd, in the place where Hashem will choose to establish the divine name. You shall not eat anything leavened with it; for seven days thereafter you shall eat matzot (unleavened bread), bread of oni—for you departed from the land of Egypt hurriedly—so that you may remember the day of your departure from the land of Egypt as long as you live.

What does this expression mean – “bread of oni“?

In the Gemara in Tractate Pesachim we find a discussion about this: Because one way to translate oni is poverty, is this the bread of the days of slavery itself? Bread that suggests sorrow and hardship – and therefore, Egypt? Perhaps the bread of the poor man himself?

Or, as Rabbi Akiva says in the name of Shmuel:

“Bread of oni“ – referring to the root a’.n.h. – la’anot, to answer, to respond – bread about which many things can be said“. Does the bread itself tell the story of the Passover Haggadah?

Matzah is bread that does not contain oil, eggs or any kind of drink, but only water and flour. Matzah is poor in taste, but precisely this poverty makes it free from bondage to matter. Therefore – it is itself free, and thus it tells the story of slavery and redemption.

It turns out that among the three main foods on the night of the Seder – A reminder of the Passover offering, matzah and maror:

Maror – the bitter herbs – is a reminder for slavery, the bitterness which we experienced in Egypt – Mitzrayim, a place of narrowness and trouble.

The Passover sacrifice – is a reminder for freedom, for the exodus from Egypt, the ability to worship Gd in our own way, to have our presence in the Holy Land, in the Temple

And the matzah – is a reminder of both, slavery and redemption.

However – this is not enough. Matzah is also a reminder of the Torah of Israel, the People of Israel, and the Land of Israel.

In the Mekhilta (1a), the Sages expounded on verse “and you shall keep the commandments” (Exodus 12:17) – “do not read “and you shall keep the commandments” [matzot], but rather, and you shall keep the commandments [mitzvot], just as one does not delay with the matzah lest it turns to chametz making us miss the whole mitzvah, so one should not miss the mitzvah, but rather, when there’s an opportunity to do it, do it immediately”. Thus, it is explained that there is an obligation to be prompt in fulfilling a mitzvah, as soon as it chances upon us.

This is the Torah of Israel.

And the People of Israel? Rav Kook writes a moving essay comparing the People of Israel to grains of flour and semolina that, together with water, became dough.

The grains – this is our national identity as a People. Mixed together with water – an allusion to the Holy One’s higher power, because in the People of Israel – we began to be a nation together with accepting the manifestation of the Shekhina. In fact, there is no remnant in our national memory of a time when this nation lived without Gd.

Then, Rav Kook continues: “This material was brought into the fire, and became bread, the nourishing element, which continues human life in its developed form”

That is – at the time of the redemption from Egypt, the Blessed One appeared to us, and “baked” us in such a way that this dough – i.e. us – was not given an option to leaven, meaning – to separate us from Gd and/or from the Torah. This was we were given the opportunity to impart through special content, as Rav Kook says “to give everlasting life to all humanity throughout the generations from the beginning until the end at the end of days.”

And the matzah is also a reminder of the great qualities of Eretz Yisrael, the Land of Israel. The connection of the Jewish People with the Land of Israel is also unique. Other peoples are attached to their land, usually because of what the land naturally offers – because it has a certain climate, natural resources, the possibility of developing agriculture, industry, shared habits, comfort, history, culture.

Our connection with the Land of Israel is a connection of simplicity and lackness. It’s a land that is described by what it does not have: “It is not like the land of Egypt” for it is limited in water – “you shall drink water from the rain of heaven” (Deuteronomy 11:11). A Land that many will say is “poor”, like the matzah, but – it is the Land of the Holy One Blessed be He, and therefore we lack nothing in it.

And all this and more – is encapsulated in the matzah.

With the matzah, we call on everyone to come and eat with us: Ha lachma anya! This is the bread of oni, of poverty & affliction! Let all who are oppressed come and eat! Eating the matzah is an experiential lesson that recreates our story, not only as a distant historical story, but as a current and future existential matter; not only as individuals but as an entire people, who do not lose hope, who “in every generation” rises and leaves Egypt, who get up and go from a place that lacks hope, to bringing the good news of redemption.

Matzah, if chewed quickly, will feel bland, tasteless and meaningless, “like cardboard” etc., but if chewed slowly, its sweetness will be released and we will feel it in its fullness in our mouths – the sweetness of freedom, unity, and prosperity in our Land. That is why we are also told not to eat anything after the Afikoman, so that this may be the flavor that remains with us from this night forward, inspiring us to set out – together – as one, on this journey, to leave slavery, cross the sea, receive the Torah and reach the Promised Land.

Shabbat Shalom & Chag Pesach Same’ach!

סרטון עם דברי תורה לסימני הסדר (בעברית): ״עושות סדר בסדר״ – מתן השרון (מכון תורני לנשים) וגם אני, בדקה 19:38 :-)):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=soXnXBAi3F8

Making seder of the Seder – from Matan- Women’s Institute for Torah Learning (English)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1dMRL1vvbRE

my mom’s hagada from Germany 1933 & the matzah cover I made in early grade school years…