שתי פרשות, שונות ודומות כמעט בלב ספר ויקרא: אחד מספרת לנו על קדושת הכהן הגדול וקדושת היום הקדוש, יום הכיפורים, והשניה, על הקדושה של כולנו, בכל הפרטים הקטנים של החיים. כן, התשובה היא עדיין, כן….

בסוף פרק כ:26, כתוב:

וִהְיִ֤יתֶם לִי֙ קְדֹשִׁ֔ים כִּ֥י קָד֖וֹשׁ אֲנִ֣י יְהוָ֑ה וָאַבְדִּ֥ל אֶתְכֶ֛ם מִן־הָֽעַמִּ֖ים לִהְי֥וֹת לִֽי׃

ואנחנו חושבים, איפה סוף הפסוק? אבדיל אתכם מן העמים להיות לי ל…. למה??

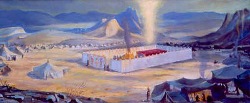

Two Torah portion, different and similar, almost in the heart of Leviticus: one tells us about the holiness of the high priest and the holiness of the holiest day, Yom Kippur, and the other, about the holiness of all of us, of our community, in every little detail of life. Yes, the answer is still yes….

At the end of chapter 20:20, it says:

And ye shall be holy unto me: for I the LORD am holy, and I will differentiate you from among the other nations, to be to me….

And we think, where is the end of this verse? I will differentiate you from the nations to be me to??? To what??

למשל בויקרא כו:12 כתוב:

וְהִתְהַלַּכְתִּי֙ בְּת֣וֹכְכֶ֔ם וְהָיִ֥יתִי לָכֶ֖ם לֵֽאלֹהִ֑ים וְאַתֶּ֖ם תִּהְיוּ־לִ֥י לְעָֽם׃

For example, ini Leviticus 26:12 it says: “I will be ever present in your midst: I will be to you your God, and you shall be to me for My people.

או בשמות יט:6:

וְאַתֶּ֧ם תִּהְיוּ־לִ֛י מַמְלֶ֥כֶת כֹּהֲנִ֖ים וְג֣וֹי קָד֑וֹשׁ…

Or in Exodus 19:6: “but you shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation….

אבל כאן? “להיות לי”, בלי סוף, כאילו בלי סיבה.

But here? “to be to me”, wito

מדרש “לקח טוב” (מהמאה ה-11, במבוסס על מדרשים קדומים) מביא כמה פירושים:

- מובדלים אתם מן העמים הרי אתם לשמי ואם לאו הרי אתם לכנענים.

- להיות לי שלא לחבר עמדי אחר שנאמר (שמות כב) בלתי לה’ לבדו.

- 3. “להיות לי” להיות עוסקים בתורתי הנתונה מנין ל”י (40) ימים.

- להיות לי שתקבלו עול מלכותי עליכם

Midrash “Lekach Tov” (from the 11th century, based on older midrashim) offers several interpretations:

1. . If you’ll be differentiated from the nations, you are for My name, and if not, then you are for the Canaanites.

2. . To be to Me, so as not to associate another to Me, as it is said (Exodus 22) “For God alone”.

3. To be to Me”- to be engaged in my teaching that was given to you over 40 days (the letter “li” in Hebrew, meaning “to me”, equal 40 in their numerical value.

4.To be to Me, that you’ll accept the yoke of heaven on you.

רב אורי שרקי אומר בדרך חיוך שכבר מתחילת הפרשה, כשכתוב “קדושים תהיו כי קדוש אני”, זה כאילו הקב”ה אומר, אני היחיד שקדוש כאן, ואני לבד. משעמם לי! בואו תהיו קדושים איתי! אלוהים מבקש להפגש בלי מתווכים, ישירות עם הנברא שלו. איך עושים דבר כזה? נכון, זה צריך הכנה. להכנס למפגש הזה מהר מידי, בלי הכנה מסודרת, כמו ההוראות שמקבל הכהן הגדול, עלול להסתיים רע (כמו במקרה של נדב ואביהו – בויקרא 10). לא להכנס בכלל, זה גם לא טוב. העולם לא נברא רק בשביל שנהיה נחמדים אחד לשני. זה חשוב, בהחלט, אבל מעבר לזה, מה עם הרוחניות? בקשת האלוהים, אומר הרב שרקי, כמו הורה טוב, תהיה בקשר.

Rav Uri Sherki says, with a smile, that from the beginning of this Torah portion, when it says, “You shall be because I am holy”, it is as if Gd says, I am the only one who is holy here, and I am all alone. I’m bored! Come and be holy with me!

G-d is asking to meet with us without any intermediaries, directly with His created. How can we do such a thing? True, this takes preparation. Entering such a meeting too hastily, without proper preparation, like the set of instructions given by the high priest, may end up badly (as in the case of Nadav and Avihu – in Leviticus 10). Then again, to not enter at all, it is also not good. The world was not created just for us to be nice to each other. Sure, that’s important, definitely, but beyond that, what about spirituality? God’s request, Rabbi Sherki says, like a good parent, be in touch.

מאוחר יותר, קורח יגיד – “כי כל העדה כלם קדושים” (במדבר טז:3), אבל זה לא מדויק. העדה, אנחנו מאמינים, היא קדושה, מצד הכלל. אבל לנו, ליחידים שבתוכה, יש עוד הרבה עבודה, איך להתאים את תכנית החיים הפרטיים שלנו למצוה הזו, להבטחה הזו, “קדושים תהיו.

Much later, Korach will say – “For all the congregation are holy” (Numbers 16:3), but this is not accurate. The community, we believe, is sacred, in general. But we, the individuals within it, have a lot of work to do, to figure out how to adapt our private life’s plan to this mitzvah, to this promise, “be holy”.

בספר בראשית (ב:7) כתוב על בריאת האדם: “וַיִּיצֶר֩ יְהוָ֨ה אֱלֹהִ֜ים אֶת־הָֽאָדָ֗ם”…. ייצר – בשני יודים (בראשית רבה י״ד:ד׳): וַיִּיצֶר, שְׁנֵי יְצָרִים, יֵצֶר טוֹב וְיֵצֶר הָרָע.

In the book of Genesis (2:7) it says, “the LORD God formed the human”… the word for formed – “vayyitzar” is written with two “yods” (the “y” sounding letter). Playing on this word the midrash says, this is for the yetzer tov (good inclination) and yetzer ra (bad inclination).

נוצרנו עם יצריות ויצירתיות, ועדיין כל אלה, הם בין אדם לעצמו, הנאות, גם אם מוצדקות ונכונות, אבל עדין, בין אדם לעצמו. אהבה, זה משהו אחר לגמרי. זה לדאוג ליצר, ליצריות, יצירתיות – של אדם אחר. הפרשות עוסקות ביחסים אסורים: עם מי לא להיות. הרשימה ארוכה ומסובכת. זה לא פוליטיקלי קורקט להגיד את כל הדברים האלה, ואנחנו קוראים אותה במבוכת מה.

We were created with instincts (yitzriyut) and creativity (yetziratiut), and yet all these, are between man and himself; pleasurable, even if justified and right, but still, between the human and himself. Love, is something completely different. It’s taking care of the instincts and creativity of another person. The Torah portion deals with forbidden relations: with whom not to be. The list is long and complicated. It’s not politically correct to say all these things, we’re reading it with no lack of embarrassment, sorry it talks like this…

בעצם, מה שאולי התורה מבקשת מאיתנו זה לצאת מעצמנו ולפגוש את האחר: לא את הדומה, לא את המשפחתי. לא את הזהה. את האחר. זה קשה. אנחנו לא לגמרי יודעים איך. יש לנו בקושי דוגמא אחת וגם אותה אנחנו לא לגמרי מבינים: “לִהְי֥וֹת לִֽי”, אמר הקב”ה. בלי סיבה. כי כשיש הרבה סיבות זה כמו שאף אחת מהן לא הנכונה היחידה. להיות לי, כי זה סיפור אהבה. לא תמיד מובן. לעיתים קרובות מאתגר ומאותגר מכל הצדדים. ועדין. לא עוזב. ככה.

What the Torah might be asking us is to go out of ourselves and meet the other: not the similar, not the familial. not the identical. The Other. It is difficult. We do not quite know how. We have hardly one example and we do not fully understand it: “To be”, said the Holy One. For no reason. Because when there are many reasons it’s like none of them is the only right one. “To be to Me”, because it’s a love story. Not always understood. Often challenging and challenged from all sides. And still. It does not leave. Just so. ******

בהליכה שלי הבקר, אני רואה זרים נפגשים בפארק עם כלביהם, הכלבים ובעליהם שמחים זה לקראת זה. כבר אין מסכות בחוץ. התפרצות של אביב. ידיעה מהחדשות: משרד הבריאות מסר כי אתמול לראשונה מזה כעשרה חודשים, איש לא מת אתמול מהנגיף. בבתי החולים ברחבי הארץ ישנם עדין 160 חולים שמצבם קשה, מהם 97 מונשמים. 6,346 מתו מפרוץ המגפה. שר הבריאות מסר היום כי ישראל חצתה את רף 5 מיליון המחוסנים במנה שנייה.

צריכה להיות ברכה לזמן הזה, משהו, שנזכור שזה שעכשיו שוב מצפצפים לנו בכביש, זה סימן טוב.

During my morning walk, I see strangers meeting in the park with their dogs. The dogs and their owners are happy seeing each other. There is no more the need to wear masks out there. Spring erupts. Some news: “The Ministry of Health said that yesterday, for the first time in about ten months, that no one died yesterday from the virus. In hospitals across the country there are still 160 patients in critical condition, of whom 97 are respirators. 6,346 died from the outbreak. The Minister of Health announced today that Israel has crossed the 5 million vaccine threshold in the second dose.”

There should be a blessing for this time, something, that to remind us that the fact that people are honking for us on the road again, it is a good sign.

Shabbat Shalom – שבת שלום