When I say that this Torah portion describes the biggest miracle in the Torah, my listener tends to think either one of us is the wrong week… but, to me, it is. Often, when we refer to miracles, events out of the ordinary, we point to things G-d has done, splitting the sea or raining manna, but If to paraphrase Rabbi Akiva in his famous conversation with the Roman ruler, Turanus Rufus, let us not worry about what’s above us (Tanchuma, Tazria 7). Because, after all, why would any of those be miracles? They were all made by G-d, and G-d, by definition, can do anything! There is no “out of the ordinary” for G-d.

כשאני אומרת שפרשת השבוע הזו מתארת את הנס הגדול ביותר בתורה, מי שמולי נוטה לחשוב שאחד מאיתנו הוא בשבוע הלא נכון … אבל בעיניי, זה כך. בדרך כלל, כאשר אנחנו מתייחסים לנסים ולאירועים חריגים, אנו מצביעים על דברים שאלוהים עשה, קריעת ים סוף או מן מהשמים, אך אם לנסח מחדש את רבי עקיבא בשיחתו המפורסמת עם השליט הרומי, טוראנוס-רופוס, אלא מענייננו מה למעלה מאיתנו (תנחומא, תזריע ז). אחרי הכל, למה שמשהו מכל אלה יהיה נס? כולם נוצרו על ידי אלוהים, ואלוהים, בהגדרתו, יכולים לעשות הכל! כך שאין באמת “אירוע חריג” בשביל אלוקים.

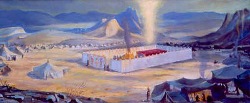

The real miracle therefore, is when we do something “out of the ordinary”, and here it comes, almost lost, almost unnoticeable within all the details, but after two and a half Torah portions with instructions how to build the Tabernacle, we’re about to actually begin the project. And the miracle? The Children of Israel are listening, following directions, and together building this most amazing construction project the world has ever seen.

הנס האמיתי, אם כן, הוא כאשר אנחנו עושים משהו “לא שגרתי”, וכאן זה מופיע, כמעט אבוד, כמעט בלתי מורגש בין כל הפרטים, אבל אחרי שתיים וחצי פרשיות תורה עם הוראות איך לבנות את המשכן, אנחנו סופסוף עומדים להתחיל את הפרויקט. והנס? בני ישראל מקשיבים, עוקבים אחר ההוראות, ובונים ביחד את פרויקט הבנייה המדהים ביותר שראה העולם.

What? “Most amazing”?? You mean, more than the pyramids or Taj Mahal?? Yes. Oh, just because it’s “yours” you think it’s so special?? No. For one, because, no one was enslaved or had to die to build it; because no one had to rob anyone or anything to make it. Because people were asked, not commanded! To bring what “their heart moves them to do”. And they did. And somehow, when all that was put together, along with the fabulous quality of wisdom, mentioned over and over again, voilla!! A place, not to honor some humanly fleeting king, or queen, was fashion, but one to connect heavens and earth, to allow that connection to flourish, which is a miracle in and of itself! And here, an “amplifier” was designed to enhance it.

מה? “הכי מדהים” ?? את מתכוונת, יותר מהפירמידות או טאג ‘מאהל ?? כן. אה, רק בגלל שזה “שלך”, לכן את חושבת שזה כל כך מיוחד ?? לא. קודם כל, כי אף אחד לא היה משועבד או נאלץ למות כדי לבנות את המשכן; כי אף אחד לא היה צריך לשדוד מישהו או משהו כדי לעשות את זה. כי אנשים התבקשו – לא ציוו עליהם – להביא את מה שלבם “ידבנו”. והם עשו זאת. ואיכשהו, כשכל מה שהביאו הורכב ביחד עם איכות החוכמה הנהדרת, שהוזכרה שוב ושוב, הנה!! הוקם מקום, לא לכבוד איזה מלך או מלכה אנושיים חולפים, אלא מקום לחבר שמים וארץ, כדי לאפשר לקשר הזה לפרוח, וזה שבכלל יש אפשרות לקשר כזה, זה כבר נס בפני עצמו! וכאן, הוא מקבל “מגבר” משמעותי כדי לשדרג אותו עוד.

In Exodus 40:2 we find: בספר שמות, פרק מ, פסוק 2 כתוב

בְּיוֹם־הַחֹ֥דֶשׁ הָרִאשׁ֖וֹן בְּאֶחָ֣ד לַחֹ֑דֶשׁ תָּקִ֕ים אֶת־מִשְׁכַּ֖ן אֹ֥הֶל מוֹעֵֽד׃

On the first day of the first month you shall set up the Tabernacle of the Tent of Meeting.

According to tradition therefore, the day the mishkan was set up, was the 1st of Nissan, this Saturday night (and always in close proximity to this Torah portion). In the Tunisian and Libyan Jewish communities this day is celebrated with special food called Bsisa. Some say wikipedia…) that “the food is powder that consists of wheat and barley, which represents the mortar used to build the Mishkan”, but the Mishkan was built of cloth (which the women wove off the goats!) and not of mortar. What the food does represent is the offerings of wheat and oil that were brought at the Mishkan, and later in the Temple. During the celebration, the whole family gathers at the home of the head of the family. The bsisa, which has been prepared well in advance, is at the head of the table, and, with special blessings, is mixed using a key, symbolizing “opening” the (Biblical) new year and especially, the gates of sustenance.

לכן, על פי המסורת, יום הקמת המשכן היה הראשון לניסן שיחול במוצאי שבת זה (ותמיד בסמיכות לפרשת השבוע הזו). בקהילות יהודי תוניסיה ולוב נחגג יום זה עם אוכל מיוחד שנקרא בסיסה. יש האומרים (בוויקיפדיה…) כי “האוכל הוא אבקה שמורכבת מחיטה ושעורה, המייצגת את החומר ששימש לבניית המשכן”, אך המשכן היה בנוי מבד (שנשים טוו את העזים!) ולא מחומר. מה שהאוכל כן מייצג הוא מנחות הסולת הבלולה בשמן שהובאו במשכן, ואחר כך בבית המקדש. במהלך החגיגה כל המשפחה מתכנסת בביתו של ראש המשפחה. הבסיסה, שהוכנה זמן רב מראש, נמצאת בראש השולחן. יש ברכות מיוחדות ומערבבים את הבסיסה באמצעות מפתח המסמל “פתיחה” של השנה החדשה ובעיקר את שערי הפרנסה.

For us, it’s been quite a year. There’s been pain and anxiety, heartache and adjustments we didn’t think would come our way. But somehow, here we are. Even if you’re not a Tunisian Jew, it’s a great time to celebrate this new month, leaving Egypt and reconnecting with the Divine. Shabbat Shalom.

עברה שנה די עמוסה. עם כאבים וחרדות, כאב לב והתארגנויות מחדש שלא חשבנו שאי פעם יקרו לנו. אבל איכשהו, אנחנו כאן. גם אם אינך יהודי תוניסאי, זה זמן נהדר לחגוג את החודש החדש הזה, לעזוב את מצרים ולהתחבר מחדש למה שאלוהי. שבת שלום

סדר נשים – חיפה -Women’s Seder, Haifa